Tips for Practicing Singing: A Practical Guide to Vocal Development

In this article, I have attempted to cover the major areas of vocal skill building, and have included at least one practical exercise for developing each of these skills. These exercises should be transposed according to the singer's voice type and range, as well as the specific area of the individual singer's range which is being targeted in the exercise (e.g., chest register, head register, primo passaggio, etc.). It is important to note that a singer will not automatically improve by merely attempting these exercises over and over again if he or she is applying incorrect technique to them. If the most basic technical skills are lacking, then repeating the same exercises will likely produce the same, or even worse, results, as vocal fatigue, strain or injury may occur due to misuse of the vocal instrument. These are exercises that can be added to an existing vocal workout program or used to supplement the vocal training provided during lessons with a singing instructor.

This guide, along with the specific exercises contained in it, is not intended to take the place of professional voice training. More often than not, improvement is more rapid and steady when a singer has a knowledgeable and skilled vocal instructor helping him or her to develop his or her vocal instrument. However, I do understand that many of my readers are currently between teachers, or choose not to invest in private voice lessons for a variety of reasons, and are actively seeking helpful advice and sound guidance in how to improve in specific areas of vocal performance.

It should also be understood that this article is not an attempt at outlining a complete or systematic approach to voice training. Such a feat would be beyond the scope of this relatively brief article. I have merely made some suggestions that may or may not compliment the singer's current voice study program or fit the singer's current needs.

Readers may contact me for more specific information or advice on how to achieve their vocal improvement goals or to inform me of any detail that might be missing in this overview. As always, please understand that it would be difficult for me to diagnose any technical errors or vocal health issues when I cannot listen to and observe a singer in person. However, I can make 'educated guesses' or assessments based on the information with which I am provided, as well as what I have learned from my years of teaching and research, and then provide information and practice tools.

GETTING STARTED

BE HEALTHY

First, a singer needs to take good care of the voice and his or her entire body before singing even begins. The singer should eat a nutritionally balanced and healthy diet. Good nutrition and adequate rest boost the immune system, helping a singer to avoid colds and other health problems that will affect his or her voice usage.

A singer should also exercise aerobically in order to increase lung capacity and stamina, and avoid cigarette and marijuana smoke, as they dry out and degrade the function of the lungs and vocal folds, which in turn makes breath management during singing less effective and voice quality less than optimal. Having good lung capacity will help especially during performances in which a singer moves around on stage with high energy or dances while singing.

Hydration is very important to helping the voice function at its optimum for lessons, rehearsals and performances. Ideally, the body should remain well hydrated, preferably with water, throughout the day, and the singer should not wait until the practice session before drinking water. During singing tasks, room-temperature water is ideal, as cold water has a slight numbing affect on the throat and makes it more difficult for the vocal instrument to work effectively. Avoid allergens that may cause throat irritation or nasal congestion, and medications that may have a drying effect on the throat.

For more tips on how to care for the voice and how to cope with specific vocal health issues, please read Caring For Your Voice.

BE SAFE

Above all, a singer needs to use correct singing technique in order to ensure that the voice is healthy and can be used for many years.

There should never be any feeling of discomfort or pain when singing or vocalizing. If a singer feels pain or discomfort, he or she should stop singing immediately. Pain is always a sign of unhealthy singing technique. Do not believe for one moment that the old 'no pain, no gain' adage should also apply to developing the singing voice. Some methods of training will even go so far as to encourage the singer to dismiss certain discomforts and pain while learning a new contemporary vocal effect or technique, assuring them that the discomfort and pain will eventually go away after they've become accustomed to using their voice in a certain (I dare say questionable) manner. If the pain is persistent, the voice should be rested, and a medical throat specialist (ENT or otolaryngologist) should be consulted, as this may be a sign of more serious damage to the vocal folds. Note that, when the voice is begin used properly, there should never be any need for vocal rest and recuperation after singing.

In many cases, singers notice more subtle changes in their voice quality without any pain or discomfort. Hoarseness, unsteadiness, an inability to sing at a softer volume, a voice that cuts out, range limitations, etc. are all signs of potential fatigue, strain or injury, not merely sources of frustration. If the singer experiences any of these changes in voice quality or function, even if they are not accompanied by pain or discomfort, he or she should seek immediate rehabilitative help, as continuing to use the vocal instrument incorrectly could lead to more and more serious vocal problems, including some that may become permanent.

If the singer finds that he or she requires days of rest between rehearsals or performances, this is also a sign that the voice is being worked incorrectly, not necessarily that it is being overworked, (although the latter may also be true). If the pain is present only at certain places in the singer's range, such as in the upper range of the voice, the singer should immediately descend the scale again and re-examine his or her technique in the notes preceding the spot where the pain began to present itself, paying special attention to even the most subtle signs of tension and strain. (Remember that upper range will not be increased when incorrect technique is being used, and it therefore makes no sense to keep pushing the voice higher when it is painful or evidently squeezed. It would be best to sing only within comfortable range until the singer's technique has been corrected.) A knowledgeable vocal technique instructor will be able to assess the problem and provide practical tips and exercises for eliminating it in the future. Learning good technique will help a singer cope with the intense demands of a busy singing schedule so that he or she will be able to continue performing without the need to cancel gigs or concerts.

WARMING UP THE VOICE

When the singer is ready to begin practicing, he or she needs to take some time to slowly warm up the vocal instrument so that it is ready for the demands that are about to be placed on it. Just as an athlete would never begin a training session without first stretching and loosening his or her muscles, it is never recommended that a singer jump into intense vocal demands without first allowing the voice to properly warm up.

I am frequently asked how long a warm-up routine should be. My answer is always that the length of a warm-up routine is entirely dependent on the individual, and even that may change with the day, time of day or season. Some singers require a half hour before they feel as though their instruments are sufficiently 'limber', while others feel as though ten minutes of easy vocalizing suffice. The kinds of singing tasks (style, repertoire, tessitura, etc.) that will follow may affect the length of the warm up. A classical singer who vocalizes mostly in high lying tessituras, for example, may require more time to warm up than a singer of a contemporary genre who never sings above his or her secondo passaggio. A belter may require more warm up time than someone who sings gentle children's song. The time of day in which the singer vocalizes may also affect warm up times. For example, many singers require more time to warm up in the mornings after their voices have not been used for many hours (during sleep). Other singers have seasonal allergies, and it takes them longer to break up excess mucous.

I prefer to keep 'warm ups' and 'vocal practice' in two separate categories. To me, a warm up consists of easy vocalization tasks that require little concentration or effort, and that aren't necessarily intended for improvement of technical skills (although they can certainly play a role in improvement, too). The exercises and 'vocalises' that a singer would use after warm up exercises, on the other hand, are designed to encourage the development of various technical skills, and will be more targeted and challenging than warm up exercises.

Tongue-tip trills and lip trills on arpeggios and scales are highly effective at gently warming up the voice because they employ only the thin edges of the vocal folds during phonation, allowing less of the vocal fold to be involved in phonation and making elongation and thinning of the folds (and thus higher pitches) easier, and because they encourage the breathing mechanism to quickly kick into gear, as well. In Caring For Your Voice, I explain why trills are particularly effective in greater detail.

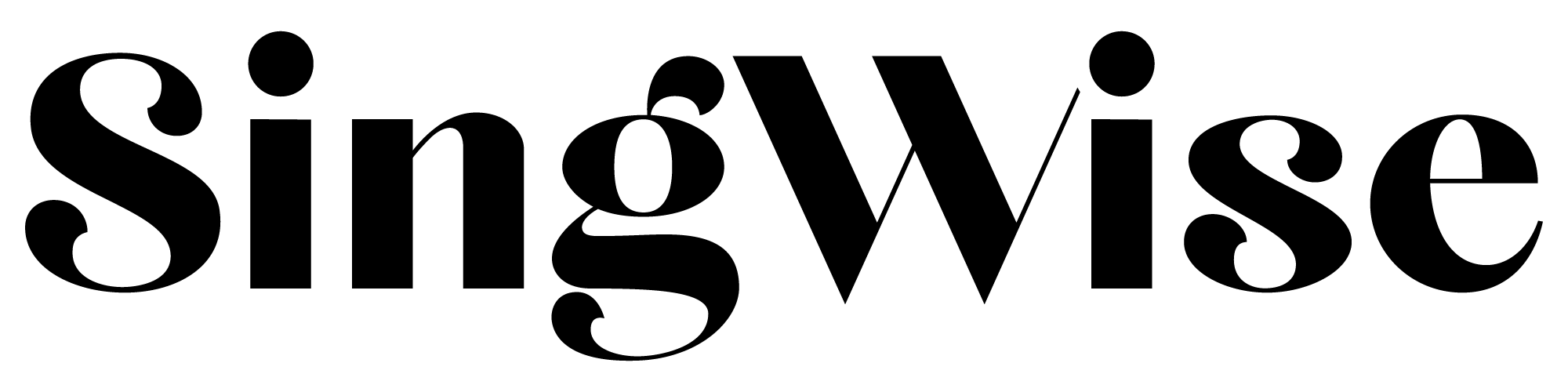

I use these two warm-ups for my students who can trill their lips and/or tongues:

WARM-UP EXERCISE 1

WARM-UP EXERCISE 2

Don't be discouraged if you find it difficult to maintain the trill throughout the exercise at first. Many students have to learn to use the correct amount of breath pressure along with the optimal degree of closure at the lip or tongue level. Practice will enable a singer to find the right balance, and thus be able to maintain a steady stream of tone during the warm-up exercises. Also, many students find that they begin to lose the consistency of their lip trills at the bottom end of their ranges, largely due to the need for less breath pressure, but also because lower frequencies (pitches) have a slower oscillatory rate. One helpful solution is to apply two fingers to the lower cheeks just outside the corners of the mouth (parallel to the space between the upper and lower sets of teeth), and then gently push up just a little, thus lifting, the zygomatic muscles. Oftentimes, what happens during lip trills is that the zygomatic muscles begin to pull down because the puckering of the lips during lip trills cause them to droop and lose their 'lift'.

If the singer is unable to do either lip or tongue trills, warming up can still be effectively done using short five-note scales that both ascend and descend in pitch singing a comfortable vowel or any combination of vowels and consonants that are easy and free for the individual singer. 'Ooh' and 'Ah' are very popular for warm-ups with my students because they are a neutral vowel and open vowel, respectively. I usually suggest avoiding longer scales and arpeggios until the voice has had a chance to loosen up because the extended range and intervallic leaps can be tension and stress inducing for the unprepared voice.

For my students who are unable to trill, I usually use this warm-up exercise on the vowel of their choice, moving up the range one key at a time, because it is easy and avoids having to hit higher pitches before the voice is ready:

WARM-UP EXERCISE 3

Triads are also effective for warm ups.

WARM-UP EXERCISE 4

Warm ups can involve nearly any kind of healthy vocalization - from lip and tongue trills to gentle sirening to simple five-note scales on a vowel sound to simple songs with small ranges - so long as they get the instrument 'loosened up' and the breathing mechanism shifted into high gear. The most important thing with warm ups is to take things slowly in terms of pitch and to use proper technique, (something often neglected or ignored during warm ups, as singers tend to think of warm ups as a quick 'practice round' before they really have to sing). You never want to sing as high as you possibly can or as low as you possibly can immediately. Start in comfortable middle range and work your way gradually to higher and lower pitches. Tongue or lip trills (rolls) are excellent for warm ups, and you can use them to cover your entire range, but your larynx must still be functioning properly and your muscles relaxed when you do them, or else you won't be helping your voice at all. So long as you are not pushing yourself as soon as you start, you should be fine.

VOCAL SKILL BUILDING

INCREASING VOCAL RANGE

One major goal of every singer is to have a well-developed and impressive singing range. A broader range means more versatility and improved artistic expression, as the singer is less likely to struggle to sing all the notes of a song in the original key. Each note within the song will sound comfortable and pleasant. However, this goal of stretching the vocal range, if not approached carefully and correctly, can present numerous risks, including vocal fatigue, strain and injury.

The key to successfully increasing the singing range is to do so gradually and healthily. A student of voice needs to avoid the temptation to rush ahead of his or her instrument, forcing it to reach for high or low notes that it is not yet ready to sing. Although a singer may be physically able to hit a certain pitch, that doesn't necessarily mean that he or she is singing it correctly. If the note sounds squeaky, shrill, breathy or strained, or if the voice cracks or the throat feels tight, uncomfortable or painful, the singer isn't yet ready to sing that note. More technical development will be necessary before these notes become easier and safer to sing.

A certain degree of technical proficiency is necessary in order for a student to effectively extend his or her upper range. If the singer is unable to access the head register due to incorrect laryngeal and acoustical function (e.g., no laryngeal tilt in the upper middle register, thus preventing the vocal folds from lengthening and thinning properly, no vowel modification, a raised larynx with an improper tilt or supraglottic compression (e.g., squeezing with the muscles of the larynx and neck), the voice will hit a proverbial wall around the second passaggio and not be able to safely break past it until proper technique is in place.

Once good technique is established, range is then gradually and methodically increased, one note (i.e., semitone) at a time, typically through short, simple exercises that use a very small range and intervals of only one half or full step at a time. It is usually best to allow each new note to be perfected - it should feel comfortable, be well supported and sound consistently pleasant - before attempting to add another note. Although it may be possible for a student of voice to sing a few notes higher or lower yet, he or she should always focus on the notes immediately above or below until they are consistently well produced, and he or she should never sing notes if the voice feels strained in any way. Having an extended range is of little use if the uppermost and lowermost notes of that range sound or feel terrible. Once the tone begins to fall apart or the voice begins to break, singing those notes is pointless - they won't be improved by repeatedly singing them incorrectly and they certainly won't impress anyone if used in a performance - and it is important to go back down (or up) in the scale and stop at the first note that begins to sound less controlled or feels uncomfortable. A student and teacher team should then examine the reasons for this loss of balanced, steady, free-flowing tone and attempt to make adjustments to and improvements in the student's technical execution of that note before moving on. Otherwise, the remainder of the scale will do nothing but deteriorate in quality, and the singer make risk vocal injury.

Many singers want to develop their ranges quickly and may have unrealistic expectations or timetables. Patience is a necessary prerequisite in vocal training. In many cases, some simple adjustments made to the student's technique (e.g., how he or she approaches a note) can produce dramatic results. I have had some students add over a half an octave to their ranges in a single lesson once they have corrected the errors that had previously been causing the limitations in their range. These results may not be typical for every singer or circumstance, however.

Although extending one's vocal range is always a noble goal, the student of voice must also understand and accept that his or her body - in which lies the vocal instrument - has certain physical boundaries or limitations unique to that individual. For example, a bass singer should never expect himself to be able to hit the highest notes of the tenor range because his physical instrument is simply not designed to do so. Similarly, a soprano will likely never be able to extend her range to the bottommost notes of a contralto's range. There is likely to be some overlapping in range between voice types, and some singers will be able to develop exceptionally broad ranges, but a higher instrument will always be somewhat more limited at the lower part of the range than a lower instrument will be and vice versa. These limitations may be a source of frustration to many singers, especially when their voice types and ranges don't fit with or get them cast for desired roles or gigs, but, unfortunately, it is an unavoidable fact of nature. All that a singer can do is make the most of the type of voice that he or she has been given, and develop as a full a range as is physically possible for him or her.

A singer shouldn't be discouraged in discovering that his or her voice belongs to a particular vocal Fach (voice type) that he or she deems less desirable, as voice classification doesn't change an individual singer's vocal abilities or place any more limitations on that singer than those that were already there before. Each voice is unique, and some singers will be able to develop extensive ranges, while others may always have a more narrow range of usable pitches within which he or she can sing, even after training. An individual mezzo soprano may be able to sing higher than a certain soprano, or an individual tenor may have access to more notes than a certain baritone might.

It should be noted that many limitations in range are due to a failure to apply the appropriate laryngeal function to the particular pitches involved. Misuse of the muscles through squeezing is also quite common. I have a student who had believed herself to be a soprano before coming to study with me. She had a well-developed and extensive upper range, and it seemed reasonable to assume that she was a soprano based on that information alone. Furthermore, she sang only in head voice tones, carrying them down as low in the scale as she possibly could (G3), thus severely limiting the lower extension of her range. Once she learned to use her chest voice, however, we discovered that she is actually a dramatic mezzo soprano with an extremely powerful chest register, and she added over five full tones to the bottom of her range - she now vocalizes as low as Bb2.

The opposite phenomenon tends to happen for students who incorrectly categorize themselves as lower vocal voice types, such as contraltos, baritones or basses, simply because they don't know how to sing in head voice. Once they figure out how to navigate the upper passaggio, they find that they suddenly have access to an octave or more above what they had previously believed to be the uppermost notes of their range. The moral of the story is that an untrained singer shouldn't assume that he or she cannot sing any higher or lower, and thus categorize himself or herself as a particular voice type, until he or she has developed enough technique to know what kind of range he or she can reasonably expect to be able to develop. (It is the locations of the passaggi, not the highest and lowest notes of a singer's range, that most accurately determine voice type. A technique instructor can help a singer to identify where these pivotal registration events occur for that individual voice, and accurately categorize the voice.)

Some of the best exercises for increasing range, particularly at the top of the scale, are simple three-note exercises on all of the five pure Italian vowels. I use the following exercise to develop both the upper and lower range:

VOCAL RANGE INCREASING EXERCISE 1

Short chromatic scales are also excellent exercises for gently and gradually broadening a singer's range because they involve very small steps of only a semitone. (When attempting to add notes to the top or bottom of the range, it is always best to avoid large intervals.) For example:

VOCAL RANGE INCREASING EXERCISE 2

BLENDING (OR BRIDGING) THE REGISTERS

Learning to blend the registers is one of the most challenging, and often frustrating, aspects of singing for most students. Most new singers have noticeable register breaks, in which their voices shift into the adjacent register with a crack or 'clunk' or change in volume or tone quality, and it takes a great deal of work and dedication to retrain the vocal instrument to make the correct acoustic and muscular adjustments necessary at every pitch to promote seamless transitions throughout the range.

In order for the vocal folds to produce higher pitches, they must elongate and become thinner, with less of the folds becoming involved in vibration. As pitch descends, the opposite occurs, and the vocal folds become shorter and more compact, and more muscular mass becomes involved. When registers are smoothly blended or 'bridged', there is a certain balance of muscular involvement that needs to become reversed around the passaggi (the pivotal registration change points). The chest register is primarily thyroarytenoid (shortener) dominant, the middle register (women) or zona di passaggio (men) are 'mixed in function', and the head register are primarily cricothyroid (lengthener) dominant. Therefore, moving from chest voice to mixed (middle) voice requires that the balance of the laryngeal muscles shifts from shortener to lengthener dominant to create and support the higher pitches. This shift needs to be gradual and continuous, or else an unpleasant register break will occur.

This gradual muscular shifting is aided by a simultaneous acoustic shift, generally achieved through subtle modification or alteration of the sung vowels and by adjustments in breath energy. In Italian, this aspect of technique is generally referred to 'aggiustamento'. When the acoustic shift begins to happen, the tone of the voice generally starts to incorporate more and more of the adjacent register's quality. For example, as a male singer moves upward through his zona di passaggio, the tone will gradually begin to sound more and more 'head voice like' and less and less 'chest voice like', and there will be a section in which both sounds are very clearly part of the mixture. Failing to allow this acoustic shift to take place over the course of the several notes preceding the passaggio, where the muscular shift naturally occurs, will inevitably cause an abrupt and noticeable change in sound (i.e., a register break).

The French term for this mixed sound quality is voix mixte. This registre mixte (mixed register) is found in the region of the singer's range that is common to both the heavier (chest) and lighter (head) laryngeal mechanisms. It refers either to an intermediate vibratory mode that borrows timbre (resonance qualities) and muscular elements from both the lower (chest) and upper (head) registers or to a vocal technique developed in the Western lyric school of singing in which singers unite or bridge their chest and head registers. Most researchers believe that this resonance balancing choice can be produced in either the lower laryngeal mechanism, (which is more common in men since they have a greater chest register range) or in the lighter laryngeal mechanism, (which is more common in women because they have a longer middle section of their range). In this sense, voix mixte is a register made in either chest or head that is coloured to sound more like the vibratory mode of the other register. Use of voix mixte allows singers to realize a homogenous voice timbre throughout their tessitura and eliminate register breaks.

The biggest mistake that I see with singers is that they attempt to learn blending by repeatedly singing the same scales quickly, with the same results each time. (Speed does not cover up, nor improve, bad sound.) They would be better served, instead, by breaking down those scales note by note. Major scales and chromatic scales that begin a few notes below the passaggio and end a few notes above it are a great starting place for learning to effectively blend or bridge the registers. A student can start out slowly, taking special note of the resonance and muscular balancing at each semitone, and feel how this balance shifts very gradually in the scale. By tackling and perfecting individual notes in the scale first, a student can usually learn to recognize the physical and acoustic signs associated with both correct and incorrect resonance and blending, make necessary adjustments, and develop effective muscle memory. Once the vocal instrument learns to consistently make the correct adjustments at every note, the range and tempo of the exercise can be gradually increased.

There are female students for whom blending is a major challenge because of the relative heaviness and fullness of their chest registers as compared to that of their middle registers. For these lowere voiced singers, their chest voice tones are full, and there is a great deal of dynamic intensity (e.g., volume), yet their timbre significantly lightens and their volume diminishes when they are singing in their middle registers. With these students, I introduce the concept of voix mixte to help them blend the colours of their adjacent registers and ultimately eliminate register breaks. (Sometimes, I suggest that they think of this section of their range as a sort of 'grey area' that is neither fully chest nor fully head, and in which they can choose to balance their tone as they see fit for a given vocal task.) I usually have them intentionally but progressively lighten up or brighten the tone of their chest register as they ascend the scale toward their first passaggio. Likewise, as they enter their middle register, I have them hold onto a little bit of the fullness of their chest register tones (but still allow for the appropriate muscular changes or register shifts where they would naturally occur) and increase their breath energy. Doing so often enables them to create a more homogenous sound between these two registers that would otherwise sound very different. Then, we work toward developing a stronger middle register. Dramatic baritones will often encounter the same kinds of challenges when they ascend the scale and enter their zona di passaggio and head register. This same blending technique is often helpful for them.

For lighter or more lyric voices and for voices of higher fachs, this same kind of blending technique is not usually as necessary, as the chest register for these voice types is not usually as 'big', creating less inconsistency between timbres as they ascend into their middle and upper registers, or descend into their chest register.

Glides, slurs and portamentos (short, smooth slides through intervals in which all the in-between notes are sung), both ascending and descending in pitch, can help the student learn to make smooth laryngeal adjustments. For example:

BLENDING THE REGISTERS EXERCISE 1

BLENDING THE REGISTERS EXERCISE 2

BLENDING THE REGISTERS EXERCISE 3

BLENDING THE REGISTERS EXERCISE 4

These slides should be made slowly, and the tendency to rush through the second half of the descent should be avoided. (I liken this to a roller coaster ride. At the top of the coaster's hill, the car is moving forward, but slowly. As it begins to descend the hill, however, the car picks up more and more momentum and thus speed. The voice tends to do the same thing when descending in pitch.) It's a particularly good idea to practice gliding smoothly and with control through the passaggi, as this is when it is likely to be the most difficult. If the passaggi are problematic and the student experiences a 'clunking', he or she should try a short, chromatic scale, such as Vocal Range Increasing Exercise 2 (above), and apply it in the area of the passaggio in order to master the acoustic and muscular shifts associated with each individual note in the scale. Use all of the five pure Italian vowels.

There are many examples in both classical and contemporary repertoire in which singers are required to slide from (or 'tie') one note to another during a single word or vowel phoneme rather than sing each note in isolation. Practicing vocal glides will help to develop the necessary control to use them during the singing of text.

Two of my favourite exercises for teaching blending of the registers once a certain mastery of the passaggi has been achieved involve a gradual 'back and forth' climb and descent that cover a little more than an octave in range. The goal is to avoid the 'stair stepping' or 'zigzagging' sound in which the voice shifts very dramatically from pitch to pitch. To avoid this, the singer needs some control over his or her instrument. To illustrate the difference in the smoothness and control that I desire to hear, I sometimes tell my more visual students to think of their voices floating gently like a leaf in the wind, or climbint an escalator rather than climbing the stairs.

Some students also have a tendency to emphasize certain notes, usually the lower notes, more than the others in the exercise. These notes will often sound louder or be better articulated than the others - I call is this 'revving' - and the student needs to learn to maintain both steadiness of volume and consistency of articulatory definition.

BLENDING THE REGISTERS EXERCISE 5 (PART 1)

Then, after taking a breath, the exercise continues with ...

BLENDING THE REGISTERS EXERCISE 5 (PART 2)

Different combinations of vowels and consonants can be used in these exercises, such as 'Gay'.Dah' and 'Nay Nah'. Singing the exercise on single, sustained vowels, such as 'o' or 'e' adds a little more of a challenge to the exercise.

Another variation to this exercise, which involves a little more breath control due to its being a bit longer, is:

BLENDING THE REGISTERS EXERCISE 6

Another exercise that extends through different registers and also develops the singer's ability to smoothly execute (short) intervallic leaps is:

BLENDING THE REGISTERS EXERCISE 7

The challenges for most students with this exercise include staying on pitch, maintaining smoothness of the legato line and finding consistency of timbre between the registers. In addition to demanding laryngeal flexibility, this exercise can also help to develop vocal agility. (It's one of my favourite multi-purpose exercises.)

To learn more about blending the registers, please read Blending the Registers in Good Tone Production For Singing, as well as Register Breaks and Passaggi in the Glossary of Vocal Terms and the article on vowel modification.

I have also just written an article on Eliminating Register Breaks that offers more explanation of the possible causes of register breaks and practical tips on how to even out the singer's scale.

IMPROVING TONE

I have dedicated an entire article to Good Tone Production For Singing, which discusses numerous common technical faults and how to correct them, as well as what good tonal balance (chiaroscuro timbre) means. Singing With An Open Throat: Vocal Tract Shaping covers such aspects of tone production as opening up the authentic resonating spaces of the vocal tract and encouraging the presence of both lower and upper harmonic overtones in the voice, (characteristic of balanced tone), by assuming ideal positions and shapes of the vocal tract. Correct Breathing For Singing also explains how good breath support and efficient tone are connected.

Many of the same exercises described above and below can be used to develop tone in all areas of the range. My suggestion is to always work on improving the tone of the voice note by note, not attempting to sing a broad range of notes over and over again hoping for different results without making any real changes to technique. Each note of the scale should have an acoustical balance that creates a pleasant, fully resonant sound and ease of production (e.g., no discomfort or feeling of tightness or tension). The key is to always be patient when developing aspects of technique, mastering the entire range one single note at a time.

Readers often e-mail me asking how they can improve their tone in specific areas of their range, and most commonly in their head registers. What I have written in the other articles on the SingWise site should give them a good starting place, but sometimes they hit a plateau and need even more guidance.

Once the most important elements of healthy vocal technique, like breathing and correct postures of the vocal tract, are in place, the singer can then turn his or her attention to further improving head voice tone. If a singer is struggling to sing above his or her secondo passaggio with ease and comfort due to technical errors, for instance, developing tone in this higher register will be impossible. The laryngeal tilt and vowel modification need to be in place in order for the larynx to remain lower and for the vocal folds to stretch and thin properly, giving rise to higher pitch. Once the student finds singing these pitches comfortable and easy, he or she can then begin the task of resonance tuning or formant tuning, which is the process of balancing out the higher and lower harmonic partials of the voice. The singer will soon begin to recognize when these overtones are present (e.g., the voice will have a fully resonant and vibrant 'ring' to it), and when they are absent (e.g., the tone will sound almost 'one-dimensional', flat, dull, overly dark in colour or overly bright or shrill). Then, with the help of a voice instructor who can offer feedback and tips, the singer can make the subtle adjustments of the vocal tract that are necessary to consistently encourage this tonal balance. Finding this balance every time will become easier with practice.

One exercise that I use for some students to reinforce their upper middle and head registers involves singing staccato then legato. Staccato often helps a singer to find the correct acoustical quality for the pitch that can then be reproduced in legato singing. The exercise below can be sung first in staccato and immediately repeated in legato in the same key. The staccato portion of the exercise can later be removed when the student successfully sings each note with good tone. This exercise involves a variation on a short major scale, making it easy to focus on tone development because of the simple, recognizable pattern and the short intervals.

IMPROVING TONE EXERCISE 1

IMPROVING PITCH: EAR TRAINING AND HARMONY

Singing on pitch can be both an easy and a challenging skill to gain, depending on the student and the vocal circumstances. For instance, some students have problems hearing or reproducing pitch accurately, as they may be tone deaf. Other singers may experience unwanted pitch deviations only at pivotal registration points (the passaggi) due to their incorrect navigation of the ascending scale (referred to as 'static laryngeal funtion') - this is the most common reason for pitch errors that I encounter in my studio. Many singers find that simple, nearly predictable melodies are easy to sing pitch perfectly, but then they struggle with pitch once the melodies become more complicated or require larger intervallic leaps and thus greater technical proficiency. Still others have a fine ear for pitch, but are so self-conscious about singing in front of others that they doubt their abilities to sing on tune and worry that the tone of their voices will sound unpleasant to others, especially in the higher area of the range. (I have dedicated an entire article to tone deafness and other causes of persistent pitch problems that may be worth reading if pitch errors are frequent occurrences for you.)

If a singer struggles with pitch in general, it is best to begin with developing his or her ear by starting out simple. Basic five-note, then one octave, major scales are a good place to start, as most people are familiar with and feel comfortable with the predictability of such patterns. If the singer can manage these scales successfully without deviating from the pitch, then he or she is not truly tone deaf, and developing an ear for pitch will be relatively easy. Eventually, arpeggios and more challenging melodies, as well as scales in minor keys or modes, for example, can be attempted. The student needs to learn to be able to recognize the presence of both discordant and harmonic sounds. It is often easiest to hear pitches on a piano/keyboard or an acoustic guitar.

If 'pitchy-ness' is a significant problem for the singer, that singer should not attempt to teach him or herself how to recognize correct pitch until after it has been confirmed that he or she can indeed hear the differences between pitch perfect notes and sour notes. If a vocal instructor is not available, a friend or family member who has a good ear for music can help the singer by verifying when pitch is correctly matched. If the singer can consistently tell when he or she strays from the desired pitch, the problem is likely more technical in nature, and is most easily remedied by some exercises that will improve how the singer navigates the scale.

I have one very young student who used to consistently go flat around B3 (the B immediately below middle C), and couldn't sing any lower. Her pitch was perfect above this point. This note is not the lowest pitch that even a soprano can sing, so I knew that she should be able to sing a little lower in the scale yet. I soon learned that the problem was that she was not accessing her chest register at all, and was attempting to carry her head voice down as low as possible. Once she began to use her chest voice function, however, her problems with pitch at the bottom of her scale disappeared, and she gained another half octave in range.

When it comes to harmony, there are many different approaches to teaching and learning the skill. I have compiled a list of Recommended Resources for my readers that can be purchased through Amazon. Some of these books and training programs are dedicated to teaching singers how to harmonize. Harmonizing is a useful skill to have, particularly in contemporary genres, whether the singer is singing back-up vocals live or in the studio either for himself or herself or for another singer, or whether he or she likes to add some harmony lines even when singing lead in order to add some drama to the lead melody line. Of course, having an ear for harmony is also necessary in choral settings where the group is divided into four or more different voice parts.

Simple exercises in which a chord is played and the singer attempts to select one of the notes to sing (i.e., the third or the fifth note of the scale) may initially help to develop the ear to hear and come up with basic harmonies. The teacher should sing the melody note or line so that the student has a point of reference and can learn not to get thrown off pitch by hearing other notes of the scale being sung simultaneously.

I've noticed that there seems to be a link between singers who were regularly exposed to multi-part harmony early in life and their ability to harmonize easily as adults, although I have no published scientific research to back up this hypothesis, and this note should not be misconstrued as a prediction of one's ability or inability to learn how to harmonize.

Many of my students sing in choral ensembles at church or school or in community choruses, and this provides a great opportunity for them to learn how to harmonize (if they are not singing the soprano part, which is generally the lead melody of the song). A group setting is pressure free, as no individual voice stands out from the group, and if an individual singer deviates from the harmony line or has difficulty finding it, there are other singers around him or her who can get that person back on track. Every one of my students who sings in a choir has claimed to have become much better at harmonizing with each season spent singing with their groups.

I also encourage my students wishing to learn to harmonize to begin listening to groups, such as barbershop quartets or southern Gospel vocal bands who rely very heavily upon multi-part harmonies for their sound and style. With these groups, harmonies are generally very easy to pick out and easy to follow. Early pop music from the 1950's and 1960's also made use of a lot of harmony. Even if these styles of music aren't particularly appealing to a given student, they can still make a great educational and practice tool. Also, getting into the habit of singing harmonies to the songs on the radio or one's CDs or I-pod instead of always gravitating toward the lead melody is a really good one to get into because, as with anything in life, we learn and improve most through practice and repetition.

For even more practical tips for correcting pitch inaccuracies and improving overall pitch matching, please read Ear Training For Teachers in my article entitled Tone Deafness (Amusia) and Other Causes of Persistent Pitch Problems.

DEVELOPING AGILITY, VOCAL FLEXIBILITY AND VELOCITY FACILITY

A more advanced skill for vocal students is gaining agility or flexibility of the voice. Agility enables the singer to execute melodically complicated passages and lines with ease, good tone and control in both the upper and lower extensions of the voice. Agility allows for more interesting embellishments and melismatic vocal runs - the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. (Although most contemporary genres are more text driven and syllabic, where each syllable of text is matched to a single note, in approach and therefore don't require such vocal agility, it is nevertheless a very practical skill to have.)

An ability to both sustain and move the voice is acquired through systematic voice training. Agility factors should be introduced relatively early, once a basic control over singing technique and function is obtained. Velocity facility must be acquired in order for sostenuto (sustained) singing to become totally free. The mastering of melismatic lines can be accomplished through the vocal gymnastics of advanced technique building exercises.

Start with brief, rapid agility patterns built on scale passages in comfortable low-middle range, first in staccato fashion, then legato. Agility patterns are freedom inducing in nature. They are intended not solely for voices singing literature that calls for frequent coloratura and fioritura passages, but for voices of every Fach (type) and for singers of all styles. (It should be noted that certain voice types are naturally more endowed with agility abilities, with lighter voices often having an easier time with agility passages than lower voices with more weight. However, this doesn't preclude singers of other voice types from developing agility.)

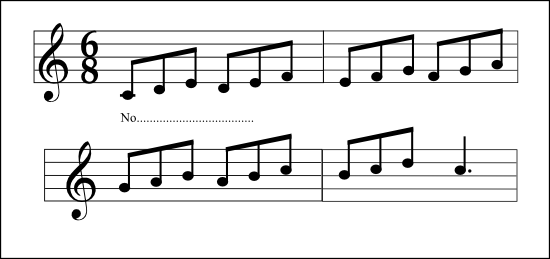

The exercise below is particularly useful for developing agility in the upper middle and upper part of the range:

AGILITY AND FLEXIBILITY EXERCISE 1

Try the combination of Ti-Na, then Ti-No and Ti-Nay. Use the sustained note to establish good tone (e.g., to find the correct "placement" or acoustical balance), singing the note for as long as is necessary, before proceding to the more rapid part of the pattern. Be sure that each note on the higher part of the exercise is well produced before moving up to the next key.

Another exercise that also develops the singer's ability to smoothly execute (short) intervallic leaps is:

AGILITY FLEXIBILITY FACILITY EXERCISE 2

The challenges for most students with this exercise include staying on pitch, maintaining smoothness of the legato line and finding consistency of timbre between the registers.

IMPROVING BREATH SUPPORT AND INCREASING STAMINA

In my article on this site entitled Correct Breathing For Singing, I explain the body's natural way of taking in breath and supporting the tone of the voice. I have also included several basic exercises to help the beginning singer learn to breathe diaphragmatically.

It should be understood that breath management and tone are interrelated. If the singer's tone is unfocused (e.g., 'breathy'), for example, air is lost too quickly due to inadequate closure of the vocal folds. It 'leaks' out between the separated folds instead of facing healthy resistance at the laryngeal level and being used up in a slow, minimal, steady stream. In pressed phonation, air is expelled too rapidly from the lungs in an effort to push apart vocal folds that are too tightly closed. Too much air is used up at the onset of sound in order to set the vocal folds vibrating to begin phonation (making sound), leaving the singer with less air for the remainder of the sung phrase. In both cases, excessive amounts of air are used up during the sung phrase, and until these aspects of tone (e.g., vocal fold closure problems) are improved, the singer will continue to lack stamina or endurance.

One very common mistake that many singers make is using up more air than they need for a given vocal task. In an effort to make their voices sound more powerful, they force the air out of their lungs as rapidly as possible. They confuse increased breath usage with improved breath support, and they end up pushing rather than allowing the air to flow out in appropriate levels (amounts) and at an appropriate rate. Doing so may put stress on the vocal folds, will impede resonance and thus natural volume, and will certainly reduce the amount of air available at the end of the vocal phrase. Remember that tone should ride on a steady and minimal stream of breath. It often takes a while for singers to figure out just how much air they truly need for a given vocal exercise or phrase.

Newer and untrained singers also have a tendency to inhale as deeply as they can - this is often referred to as 'tanking up' for a vocal task - even for a short exercise or phrase, then push out as much air as they can while singing the phrase because they falsely believe that they need to use up all that air in order for the tone to be "supported" well. Then, they inhale again as deeply as they can for the next short phrase. Within a few breaths, they find themselves feeling lightheaded or dizzy because their poor breath management has led to hyperventilation. I sometimes have to remind my students that they can either breathe less deeply for short phrases, or choose not to take a breath between two short phrases. Having less air in the lungs initially - just enough to sing the phrase comfortably and not feel as though they are going to run out of breath at the end - usually prevents them from trying to push all the air out of their lungs as fast as they can. Pushing out more breath does not create more vocal power. Instead, it leads to strain and a forced sound, as well as less endurance - you'll always run out of air too quickly. Learn not to waste your air, and use correct vocal posturing to obtain optimal resonance.

For students who are struggling to use their breath correctly, I will sometimes have them go home and practice sustaining a note - a comfortable pitch for each individual - at a full volume (not shouting, though) for as long as they can. I warn them not to allow themselves to get to the point where they feel as though there is absolutely no air left in reserve because they will inevitably feel the desperate need to inhale loudly and quickly at the end of the sustained note - to gasp for air - which means that they are not learning to control their breathing well enough, as the whole body will often tense up while taking the next breath. Oftentimes, this exercise will help the singers stop pushing air out faster than is necessary, and they quickly learn to use their air more sparingly. Above all, they learn that using a lot of air and breath pressure is not conducive to maintaining a steady stream of tone - in fact, usually the opposite result occurs when they are forcing, as the tone is shaky or unsteady, the volume is inconsistent and the vibrato rate is unhealthy and variable. They usually return the next week feeling very encouraged by their findings and improved breath management skills.

In general, any exercise that requires either an extended series of notes to be sung on a single breath or long sustained notes (or both in combination) can help to develop breath support and improve the singer's ability to sing for longer on a single breath, so long as good (efficient and clear) tone is in place. A long exercise pattern, such as Blending the Registers Exercise 6, can be gradually slowed down over time so that the singer can be increasingly challenged to use his or her breath more and more efficiently. As the muscles involved in breath support become stronger, the singer will find that he or she is able to sing these exercises more easily, as well as sustain notes for longer and sing longer vocal phrases without the need for taking a breath mid-phrase.

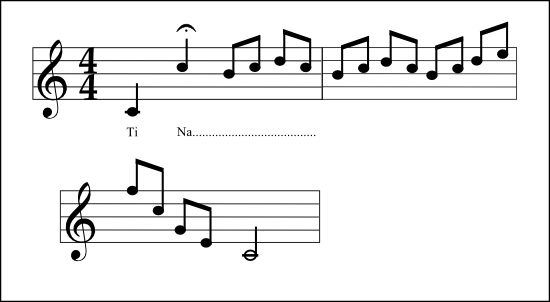

The following exercise is intended to train the singer in appoggio technique, which is designed to slow the rise of the diaphragm so that air is retained in the lungs for longer and used up more slowly. The entire exercise should be sung on a single breath. With each section of the exercise, the muscles that support inhalation should be encouraged to return to their initial positions, with the upper abdomen and lower ribs expanded as much as they were at the time of inhalation, thus preventing the premature rise of the diaphragm, as well as strengthening the muscles. The mezzo-staccato (dotted) notes should be sung with no breath taken in either before or afterwards, but with the abdominal muscles moving outward as though inhalation is occuring during them. Different vowels should also be tried. Remember that the clearer the tone of the voice and the slower the rise of the diaphragm, the more breath will be available to sing the entire exercise. If you run out of breath at some point during the exercise, either speed up the tempo of the exercise a little so that you are able complete it on a single breath or sing as far into the exercise as you can, then take a very small, quick breath between notes so that you can finish the pattern. In time, your stamina will improve, and the length of the exercise will no longer seem so daunting.

BREATH SUPPORT AND STAMINA (APPOGGIO TECHNIQUE) EXERCISE 1

ENCOURAGING HEALTHY VIBRATO

I have written an entire article on the topic of vibrato and how to develop it naturally, also published on this website. As I explain in that article, I don't directly teach vibrato to my students because it often places unnecessary pressure on them to produce one, often by artificial and unhealthy means, and prefer instead to allow their vibratos to develop naturally through good technique (e.g. balanced tone, with all the overtones of the voice present, good breath support, and vocal freedom).

With that being said, however, the presence of vibrato in the voice can be encouraged through exercises that require the student to sustain a note on a single vowel sound for a measure or two. These exercises encourage correct, efficient breath management, which is also necessary for the vibrato rate to be optimal.

One such exercise is:

VIBRATO EXERCISE 1

In this multi-purpose exercise, the first five notes are sung legato (smoothly), the fifth note should be held for (nearly) a full measure. There should then be a slide (portamento) up to the octave note, which should be sustained for two full measures, or longer if the singer feels ambitious. The vibrato should be encouraged to be present at the start of the sustained note, rather than deferred until the end of it, as is customarily done in contemporary styles of singing.

Another exercise involves sustaining the note earlier in the exercise instead of at the end:

VIBRATO EXERCISE 2

As with all of the exercises that I have suggested in this article, the singer should try using different vowels and vowel-consonant combinations in order to achieve a more complete and text-applicable vocal training that more closely matches the language requirements of song text.

Vibrato is generally easier to develop in the upper middle and upper range due to the increase in breath support required, as well as the increased vocal fold tension and the decreased amount of mass involved in the vocal fold vibratory cycle. However, a singer should not neglect developing a natural, healthy shimmer in the voice in the lower part of his or her range.

The key is to not attempt to induce, force or fake vibrato, because doing so may be unhealthy, and will likely create a vibrato that doesn't sound natural. All other elements of technique, from efficient breath management to balanced tone, are the building blocks to vibrato and can't be neglected or bypassed.

APPLYING VOCAL TECHNIQUE TO SONGS

The value of technique training is often only fully realized when a singer begins to apply his or her new vocal skills to songs. The success of lessons is also gauged by how well a singer can execute the songs in his or her repertoire. Singing isn't about scales and arpeggios, which are merely practice tools for developing technical abilities that will enable a singer to sing songs of his or her choosing with greater skill and artistry, and scales and arpeggios should not be taught without also explaining what skills they are useful for building and how to apply them to repertoire.

When I'm working through songs with my students, I will spend most of our time focusing on how technique is being applied to the piece. (Since I am not a vocal coach, I don't tend to spend very much time offering guidance in how to interpret lyrics, or how to emote or gesture or arrange the music.) Students might come in complaining about particular areas of a song that they are struggling with, and I will diagnose the problem and help them develop the technique necessary to master those sections of the song. These problems are most often related to registration, pitch, breath management and tone. If necessary, we will break from singing the song and try an exercise that will help to further develop that particular technical skill.

When I personally prepare for a concert or gig, I work through each song, line-by-line, note-by-note, rather than singing the entire song from beginning to end, hoping that any problem areas will somehow be magically erased through global repetition. I want every single note to sound perfect, and every line to be flawless, and this requires breaking down the song into its smallest parts. Once those sections have been mastered individually, the entire song can then be flawlessly executed, and I'll be freer to focus on expressing the emotion behind the lyric and music and connecting with the audience when I'm performing it. It's tough for most singers to suppress their desire to sing through an entire song just for the love of singing and, instead, spend much of their initial practice time working through the tedious elements of technique and correcting the minor errors in their execution, but this kind of nitpicking and perfectionism are always worth the time and the effort in the end, when highly skilled artistry shines through in their performances.

During lessons, there are many bad or unproductive vocal habits that tend to appear for the first time when a vocalist is singing a song. For example, many singers use overly nasally tones when they are singing repertoire, even when they don't apply the same nasality to their vocal exercises. Oftentimes, singers have a tendency to nasalize non-nasal vowels. Also, many students of voice tend to forget their breathing technique when they begin to sing songs, or they struggle to find places in a song where they can inconspicuously take quick breaths. These are the kinds of technical aspects of singing that I help a singer work through and apply correctly to their repertoire.

Another common question that my students come to me with pertains to vocal registration choices. Sometimes, singers don't know if they should be singing in chest voice or middle voice in a certain section, especially in those areas of the range where either choice may be appropriate. In many cases, I help these students with their blending so that registration isn't an 'either or' or a 'black and white' issue, but a tonally 'grey' area in which they can incorporate a blended or mixed sounding tone. Sometimes, the tessitura of the song - the pitch area in which much of the song's melody is sung - is simply not suited to a singer's particular voice type or range, and the key of the song needs to be either raised or lowered. Since I know each of my student's voices very well, I can help them make the best choices in these areas.

It is important for vocal students to select songs that are a good match for their current vocal abilities. The songs should be challenging enough that they will need to work a little bit at it, (though not for so long that they become bored), and will feel a sense of accomplishment when it comes together, but not so difficult that they won't be able to sing it and become frustrated or discouraged. (I have written an article entitled Selecting the Right Songs For Your Voice that contains more practical tips on how to choose a suitable song.)

TRACKING PROGRESS

Taking note of how much one is improving (or not) is a good way for a singer to evaluate the quality of his or her voice lessons or practice program.

One valuable tool for tracking one's progress is a sound recording. Some singers will bring in a cassette tape or CD to an early voice lesson to record how they sing the vocal exercises before they have had any training, and then periodically record their lessons. Listening back to earlier recordings and comparing them to later recordings often reveals marked improvements that isn't always taken note of when progress tends to occur slowly but steadily, rather than dramatically. (It's like how a parent doesn't really notice how much his or her child is growing day by day, but when a friend or family member sees that same child after a period of absence, the growth is definitely more noticeable or obvious.)

Another way of using a sound recording to track progress is to select a favourite song and record yourself singing it onto your computer. A few months into your voice training, re-record the same song and take note of how much you have improved. In yet another few months, re-record it again. Having objective 'proof' of your progress is encouraging, and will inspire you to continue learning and developing as a singer. It will also help you to pinpoint the specific areas of improvement as well as which areas of your technique still need attention.

Hearing positive feedback from others is also helpful. For instance, it is one thing for a singer to believe that he or she has improved over time and with practice and lessons, or for a voice teacher to tell that student the areas in which progress is most notable. It's another thing, however, for family members or even fans to comment on the differences that they hear. (As a teacher, it's even encouraging for me to hear parents of my younger students tell me that they have begun to hear a significant difference in their children's voices. I don't usually solicit the feedback, but it is certainly always welcome and wonderful to receive.)

When actively seeking feedback from a friend or family member, it is important to find someone who will be honest (e.g., not overly flattering simply so as not to hurt your feelings or discourage you) in his or her assessment of your vocal skills, but also someone who will not be overly harsh and critical and who understands that your singing voice is still a work in progress. Also, you must be prepared to humbly hear and graciously accept whatever that person says about your voice. If that person genuinely cares about you, he or she will only want to help you reach your singing goals.

Keeping a training journal is also a good way of keeping track of progress, since we don't always remember the details about such things as our range or our specific limitations when we first started out singing. Early on in training, or even before starting lessons, a singer can write down, for example, his or her uppermost and bottommost notes. (If the singer doesn't have knowledge of music or play an instrument, the teacher can tell that student what those notes are.) A few weeks or months into vocal training, the singer can again make a record of his or her highest and lowest pitches, then take note of how much his or her range has increased. Specific notes about registration challenges, breath management problems and other technical issues can also be taken. Then the singer can make an entry whenever there has been a breakthrough in one of those areas, and see how far he or she has come vocally.

A diligent student might even jot down some notes during or after every lesson. These notes might include specific comments or critiques made by the instructor, new information about the scientific aspect of the vocal instrument that might have been explained, specific areas of improvement or areas that were problematic, voice function notes (e.g., vocal health related), a new exercise that was taught, its purpose and specifically how to practice it at home (e.g., the notes or pattern), any vocal health tips, products or resources that might have been recommended by the instructor, dates for upcoming recitals or auditions, etc.. During the week between lessons, a student might record how practice or rehearsal times went, or jot down the titles of songs that he or she might like to begin working on with his or her teacher during lessons.