Singing with an ‘Open Throat’: Vocal Tract Shaping

'Opening the throat' is defined as a technique whereby pharyngeal space is increased and/or the ventricular (false) vocal folds are retracted in order to maximize the resonating space in the vocal tract. Opening the throat involves raising the soft palate (velum), lowering the larynx and assuming ideal positions of the articulators (the jaw, lips and tongue), as well as shaping of the mouth and use of facial muscles.

The expression also describes the sensation of freedom or passivity in the throat region that is said to accompany good singing. The technique of the open throat is intended to promote a type of relaxation or vocal release in the throat that helps the singer avoid constriction and tension that would otherwise throttle or stifle the tone.

An 'open throat' - a misnomer for a few reasons - is generally believed to produce a desirable sound quality that is perceived as resonant, round, open, free from 'constrictor tensions', pure, rich, vibrant and warm in tone. It also produces balance, coordination, evenness and consistency, and a prominent low formant, which prevents the tone from sounding overly bright, thin or shrill. Additionally, if singing is performed with an open and relaxed acoustical space, the singer will experience a smooth blending of the registers.

This sound quality is linked to the vocal actions that take place during the preparation to sing (inhalation). The larynx lowers automatically when breath is taken in, and the soft palate naturally lifts at the same time. Because the events of singing are more demanding than those of speaking, requiring deeper inhalation, greater energy and further laryngeal depression, there is a corresponding increase in pharyngeal space that occurs somewhat naturally.

When a vocalist sings with a so-called 'closed throat', imbalance of registration is likely to occur. The chest register will be taken too high and the upper register becomes more and more harsh and strident because the singer creates a tone that is merely imitative of the head voice. Intonation becomes harder and harder to achieve because the larynx is too high and the soft palate too low, resulting in a feeling that the voice is being squeezed from both the top and the bottom. In other words, registration shifts cannot occur in a healthy manner if the throat is closed, nor if the vocal sound is driven toward the point of nasality.

The goal of every singer should be to achieve tonal balance. Many of the popular techniques that vocal teachers use to help their students improve the quality of their voices are devices for directly or indirectly enlarging and relaxing the throat during singing. The use of imagery, such as 'drinking in the breath', in their teaching is very common. Enlarging the throat space involves conscious inhibition of some of the natural reflexes, such as the swallowing reflex, a condition that is nevertheless essential to good tone production.

There is no science to refute that the teaching of the open throat is good pedagogy. The intricate relationship of muscles in the throat is positively affected when the head is allowed to be free on the neck. Each muscle achieves its proper length and connection with the others in an optimum state for functioning well. The muscles work together, each set meeting the opposing pull of the other, which allows the larynx to become poised, balanced and properly suspended. The vocal folds are actively lengthened and stretched by this action, and thus brought closer together. In these favourable conditions, they can close properly to execute the sound quickly and efficiently, and thereby produce a clear, clean tone with a minimum amount of effort. The throat is then properly 'open'.

However, relying upon the open throat technique as the cure for all singing problems is potentially shortsighted and problematic, as a 'closed throat' neither causes nor explains all vocal issues.

HOW TO - AND HOW NOT TO - ACHIEVE AN 'OPEN THROAT'

There are many opinions on how to achieve an open throat, and just as many methods of trying to create it. Unfortunately, along with the correct ideas that are backed by real acoustical and anatomical science come strange, ineffective and potentially damaging ones. The popular internet site on which numerous voice teachers claiming to be 'experts' on the topic of singing present short video clips containing advice or 'mini lessons' on how to sing is full of such ideas. I've watched video after video of teachers (whose own voices typically sound terrible) demonstrating singing technique that involves overly wide buccal (mouth) openings and other such faulty practices. (A common mistake is equating an open mouth with an open throat. In reality, a jaw that is too low actually places tension on the larynx, lowers the soft palate and inhibits the effective closure of the vocal folds, which is the opposite of the desired effect.)

I am not terribly fond of some of the methods of creating an open throat space, particularly those involving imagery or shaping of the vocal tract that encourages the distortion of vowels. For instance, yawning, which is by far the most popular approach to teaching an open throat, tends to produce an overly open pharyngeal space, and thus a hollow, 'throaty' tone. It also tends to be accompanied by a flattening or retracting of the tongue. Whenever a teacher instructs a student to yawn in order to 'open the throat', he or she overlooks the injurious ramifications of such a technique when it is applied to the tasks of singing. The yawn is not intended as a sustained maneuver for the kind of phonation that occurs during singing. Retaining the posture of a yawn, even just a partial one, during speech or song induces hyperfunction in the submandibular musculature and hinders or prevents natural-sounding voice quality.

Even when students are encouraged to only imagine and generate the first part (beginning) of a yawn, there is the tendency for the opening up to be taken too far, which may include an overly lowered jaw that is accompanied by an unhinging of the jaw joints, as in a full yawn. The tongue generally flattens, pushes back into throat and depresses the larynx, which creates a new obstruction in the singing pathway rather than freeing up the voice. We have all heard others trying to talk while stifling a yawn, and the tone and the diction are both terrible because the natural phonatory laws have been compromised by the incorrect articulation of the words. The mouth should not be overly open while singing.

If the student reaches the point where he or she really feels a hugely open space in the throat - the feeling that he or she is 'swallowing an egg' or some other piece of fruit, for example - it is actually likely that the tongue root is so out of the way of the mouth cavity that it is depressing the larynx. What is an effort to free up space for the voice to resonate better actually ends up placing tension on the throat, tightening it, and producing a hollow, throaty timbre.

Assuming a facial posture of surprise, as some teach, is just plain silly from both an aesthetic and a practical standpoint, as no singer would ever apply it during a performance because they would both look ridiculous and sound no better. Raising the eyebrows, furrowing the brow, creasing the forehead, flaring the nostrils or widening the eyes are not linked to the lifting of the soft palate nor to enhanced resonance balancing. Instead, they produce tension. These exaggerated facial postures are not to be confused with the elevation of the zygomatic muscles of the face that is associated with a more open resonating space.

If a singer would never employ a certain technique during his or her public singing performances, then it is not likely to be a useful tool to use during lessons, and it thus makes no sense to teach it. There are some exceptions, of course, but unnatural facial expressions should never be included in technical training. A singer needs to learn to adopt and vocalize with singing postures that are favourable to resonance balancing and tension-free singing. Correct vocal posturing should be the starting place in vocal training, and a student of voice shouldn't waste his or her time assuming silly facial expressions if that part of his or her technique training will later be done away with.

When I was a new student of voice, the first stage of technique that I learned was what my Bel Canto instructor called 'lifting'. I was taught to assume a pleasant facial expression (not an actual smile) during singing by gently and subtly lifting the cheeks with the zygomatic muscles - those that wrap around the sides of the mouth and lift the corners of the mouth during smiling. I remember my facial muscles quivering and twitching uncontrollably during the singing of my vocal exercises for the first several lessons as I trained them to naturally and more comfortably assume this position. Like most people, my facial muscles had a tendency to pull down somewhat during speech and singing, and the muscles needed to be strengthened and retrained.

Additionally, I was taught to 'inhale' a soft, quiet 'k' sound. (This is kind of like the imagery of 'drinking in the breath' or 'inhaling the breath'.) This technique lifts the soft palate further, separating it from the tongue, and lowers the larynx during inhalation. (Inhaling a loud or forceful 'k' sound not only makes for noisy and inefficient breathing, but it also contributes to the build up of tensions.

What I appreciate most about this method of achieving an open throat is how effortless and natural it is for the singer. It is based on anatomical science, since the soft plate naturally rises and the larynx automatically lowers during inhalation, and since a pleasant external facial posture directly affects the position of the soft palate, raising it slightly. (Yes, it's as simple as that.) In my opinion, any teaching on the opening of the throat need not go much further than this simple concept of 'lifting', as it is effective and likely to be sufficient for nearly all students.

The key is learning to maintain this initial 'open' posture of the vocal tract for the duration of the sung phrase, not allowing any tension or constriction to enter the throat. Any persistent issues with 'closed throatedness', which are most prevalent during register changes, particulary as the scale ascends into the upper middle and head registers, can be addressed if they present themselves during vocalizing. (More often than not, these tensions and technical difficulties are the result of a 'naughty tongue' and/or a raised larynx, which will be diagnosed and addressed by a trained vocal instructor.) Otherwise, a singer need only open the resonating spaces of the vocal tract in preparation for singing and then continue vocalizing with freedom in the throat.

One helpful technique for ensuring that the resonating spaces are open is using the neutral vowel 'uh' in the larynx and pharynx - that is, assuming this shape within the throat - before bringing focus into the tone and singing the desired vowel. This technique allows the open pharynx to be established first. The brilliance of the tone can then follow while the open feeling in the throat is retained. For training purposes, it often helps to actually sing the 'uh' sound, then position the tongue appropriately for the desired vowel. Sing 'uh-[e]-uh-[i]-uh-[o]-uh-[u]' repeatedly on a single breath, aiming to maintain the openness of the 'uh' while singing the other pure Italian vowels. Starting with [a] is also good, as it is a similar vowel form to the 'uh'. Once this exercise becomes easier, the student can then 'open the throat' using the (silent) 'uh' position, quickly move the tongue and the lips into position for the desired vowel, and begin to phonate on the vowel. For example, start with the 'uh' posture in the larynx and then bring the tongue forward and up as in the [i] vowel. In time, this technique will come naturally, requiring little pause for thought, and the student will be able to vocalize with an open acoustical space.

It has been my observation that whenever too much attention is drawn to what must happen at the back of the throat (the pharynx) and the larynx while singing, exaggerated results, along with unwanted tensions, are produced. I've had students come into my studio who have been taught by their previous teachers to focus so much of their attention on consciously attempting to manipulate the position of their larynxes and on actively 'opening their throats' that they end up experiencing a lot of tension in the jaw, neck and tongue, as well as a feeling of tightness and discomfort in the throat. In an effort to create more space, pharyngeal tension results as the tongue gets pushed back, and a hollow, throaty sound is produced. Registration, particularly the transition into head voice, becomes impossible because the root of the tongue depresses the larynx when it should otherwise be 'rocking' or 'tilting'.

The greatest danger of this imbalanced teaching philosophy, though, is that many students are only being offered incomplete information about vocal science and good technique. Their teachers encourage them to open their throats and lower their larynxes, but they don't actually tell them how to do so correctly and naturally, and they don't pay attention to the other components of the vocal tract, such as the tongue, that could be contributing to closed throatedness and tension. When singers attempt to locally enlarge the space in the throat, they do not actually create more space. Instead, they simply rearrange the components of the vocal tract, mostly in disregard of the laws of acoustics. When they attempt to spread the pharyngeal wall, for example, they end up tensing it. In the end, the students fail to progress and find vocal freedom because they haven't been given enough accurate information, and more harm is done than good. Stressed out and frustrated students with poor tone and unhealthy technique are the results.

The fact of the matter is that a singer needn't do anything substantially different with the jaw, mouth, tongue or larynx during singing within speech-inflection range - the range of notes that a singer would use during normal speech - than what he or she would do while speaking within the same range of pitches, (unless his or her speaking technique is also faulty). There must be constant flexibility during articulation, which is impossible to achieve if the throat is being forced to remain in one (unnatural) position during singing or speech. Instead, the spacial arrangments of the pharynx and the mouth should follow the phonetic requirements of linguistic communication. Unnatural adjustments of the vocal-tract during singing should be avoided, although some modifications of this principle occur when a vocalist sings above speech-inflection range (i.e., head register). (I explain this further in the section that discusses the unique acoustical circumstances of the female upper register in the follow-up to this article, to be posted on this site in mid June of 2009.)

In the following sections, I will focus more directly on the natural and ideal positions of the vocal tract while singing, as well as some popular, though incorrect, ways of shaping the articulators. In Part II of this article, I will examine vowels and vowel modification, and explain the concept of formants in relation to tone balance and how they are directly affected by specific vocal tract shaping.

First, however, I'd like to discuss the anatomy of the throat so that the location and structure of the individual components are not a mystery to my readers.

VOCAL TRACT ANATOMY

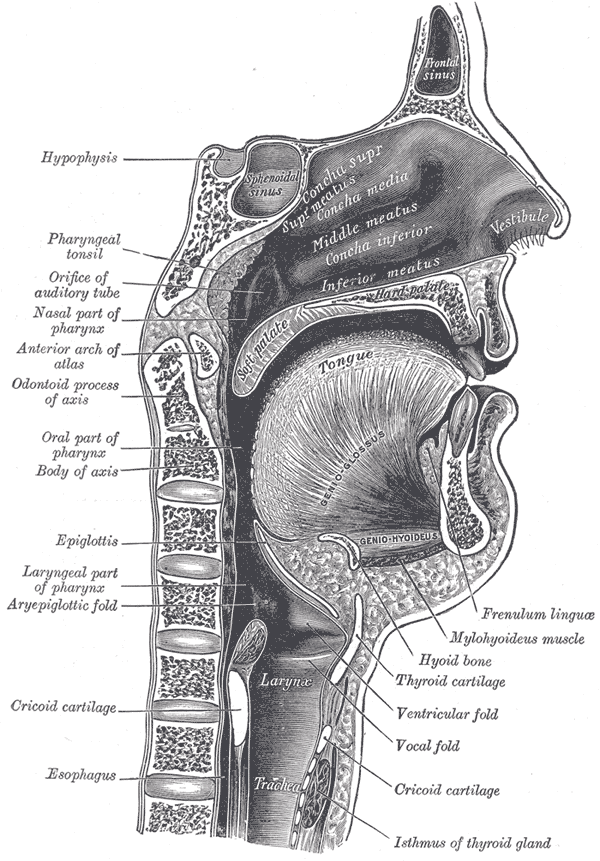

To help my readers better visualize the structure of the throat and understand the anatomy terminology that I will refer to in this article, I have included the above diagrams for study and reference. The first shows the entire vocal tract in profile. The second diagram narrows in on the structures of the larynx ('voice box'). The third diagram shows the basic structure of the soft plate and its location inside the oral cavity.

ANATOMY OF THE VOCAL TRACT

from the 20th U.S. edition of Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body

The throat, which generally refers to both the pharynx and the larynx, is a ring-like muscular tube that acts as the passageway for air, food and liquid. It is located behind the nose and mouth, and connects the mouth (oral cavity) and nose to the breathing passages (trachea/ 'windpipe' and lungs) and the esophagus (eating tube). The throat also helps in forming speech.

The throat consists of the tonsils and adenoids, the pharynx, the larynx, the epiglottis and the subglottic space.

The tonsils and adenoids are made up of lymph tissue, and both help to fight infections. Tonsils are located at the back and sides of the mouth and adenoids are located behind the nose.

The pharynx is the muscle-lined space that connects the nose and mouth to the larynx and esophagus. The pharynx extends from the base of the skull to the sixth cervical vertebra, with pharyngeal dimensions determined by the structure of the individual. The pharynx consists of three parts: the nasopharynx, lying above the lower border of the soft palate; the oropharynx, located between the soft palate and the upper region of the epiglottis, and opening out into the buccal (mouth) cavity through the palatoglossal arches - the velar region; and the laryngopharynx, extending from the top of the epiglottis to the bottom of the cricois cartilage - the lower border of the larynx. The posterior larynx projects into the laryngopharynx.

THE LARYNX

from Wikimedia Commons (Olek Remesz)

(I have also written an article detailing the structure and function of the larynx, which includes many of the structures discussed only briefly here in the paragraphs that follow.)

The larynx, also known colloquially as the 'voice box', functions as an airway to the lungs, and also provides us with a way of communicating (vocalizing). It is a cylindrical grouping of cartilages (including the thryroid, cricoid and arytenoid), muscles and soft tissue that contains the vocal folds, which produce the voice by their vibrations when they are stretched and a current of air passes between them.

The larynx is the expanded upper opening of the trachea (windpipe). The thyroid cartilage, attached to the hyoid bone or cartilage, makes the protuberance on the front of the neck known as the Adam's apple (or Eve's apple in women), and is connected below to the ring-like cricoid cartilage. This is narrow in front and high behind, where, within the thyroid, it is surmounted by the two arytenoid cartilages, from which the vocal folds pass forward to be attached together to the front of the thyroid.

From the outside of the neck, the larynx can be seen to rise when we swallow and lower when we inhale. Some elevation during phonation is often seen, as well.

The larynx is connected to the pharynx by an opening - the glottis (the vocal folds and the space between them) - which, in mammals, is protected by a lid-like epiglottis.

The epiglottis is a small flap of soft tissue and elastic cartilage that acts to cover the upper opening to the larynx whenever we swallow. It folds back and down to guard and protect the entrance to the larynx, thus preventing food, drink and irritants from entering the respiratory tract. (The larynx also aids in this closing by drawing upward and forward to close off the trachea, or windpipe, when the hyoid bone elevates during swallowing.) Food and drink are then directed to the esophagus (eating tube) instead. After each swallow, the epiglottis returns to its upright resting position - the larynx also returns to rest - allowing air to flow freely through the larynx and into (and out of) the rest of the respiratory system. The epiglottis is one of three unpaired cartilages of the larynx, the others being the thyroid and cricoid cartilages, and is one of nine cartilaginous structures that make up the larynx.

Subglottic space refers to the space immediately below the vocal folds. It is the narrowest part of the upper airway.

Supraglottic space refers to the space immediately above the vocal folds.

SOFT PALATE

from the National Institutes of Health

The soft palate (or velum, or muscular palate) is the soft tissue that makes up the back of the roof of the mouth. It is suspended from the posterior, or rear, border of the hard palate, forming the roof of the mouth. The structure is movable, is composed of mucous membranes, muscular fibres (sheathed in the mucous membranes), and mucous glands, and is responsible for closing off the nasal passages from the oral cavity during swallowing and sucking (and during the speaking and singing of nonnasal sounds).

The soft palate is distinguished from the hard palate at the front of the mouth in that it does not contain bone.

When the soft palate rises, as in swallowing, it separates the nasal cavity and nasopharynx from the posterior part of the oral cavity and oral portion of the pharynx. In sucking, the soft palate and posterior superior surface of the tongue occlude the oral cavity from the orapharynx, creating a posterior seal that prevents the escape of fluid and food up through the nose and, with the tongue, allows fluid and food to collect in the mouth until swallowed. During sneezing, it protects the nasal passage by diverting a part of the unwanted substance to the mouth.

The soft palate's motion during breathing is responsible for the sound of snoring. Touching the soft palate evokes a strong gag reflex in most people.

The soft palate retracts and elevates during speech to separate the oral cavity (mouth) from the nasal cavity in order to produce oral speech sounds. If this separation is incomplete, air escapes through the nose, causing the speech to be perceived as hyper nasally. In the case of nasal consonants and vowels, it lowers to allow the velopharyngeal port to open.

The 'fauces' are defined as the lateral walls of the oropharynx that are located medial to (through the middle of) the palatoglossal folds. The areas lateral to (to the sides of) the palatoglossal fold are not the fauces. The term 'fauces' refers to the narrow passage from the mouth to the pharynx (sometimes call the 'isthmus of the fauces') that is situated between the velum and the posterior portion of the tongue. The fauces are bordered by the soft palate, the palatine arches, and the base of the tongue. Two muscular folds - the pillars of the fauces - lie on either side of the passage.

The uvula, (Latin for 'little grape'), is a fleshy piece of muscle, tissue and mucous membrane that hangs down from the soft palate. When we swallow, as well as when we say or sing nonnasal (oral) vowels and consonants, such as "Ah", the uvula flips backward and upward, which helps close off the nasal passages (at the velopharyngeal port), preventing unwanted nasality from entering the tone.

When the zygomatic muscles are raised during inhalation, the fauces elevate as well, thus playing an important role in 'opening the throat'.

The two zygomatic muscles (major and minor) have their points of origin on the zygomatic bone and insert in the skin and muscle at the corners of the mouth. The zygomatic muscles retract and pull the lip corners upwards.

The zygomatic major is a paired muscle of facial expression that extends from each zygomatic arch (cheekbone) to the corners of the mouth. It blends with fibres of the levator anguli oris, the orbicularis oris, and the depressor anguli oris. Its participation in facial expression is determined by the emotion to be expressed. It draws the angles of the mouth superiorly and posteriorly, raising the corners of the mouth when a person smiles. It draws the angles of the mouth upwards and, as in full laughter, laterally. Like all muscles of facial expression, the zygomatic major is innervated by the facial nerve. The minor and major zygomatic muscles (assisted by the levator muscles) can raise the fascia between the lips and the maxilla (area between the lips and cheeks), much as when a fragrance is slowly inhaled through the nose, producing a pleasant facial expression, but not a full-blown smile.

VOCAL TRACT SHAPING: THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY OF VOCAL POSTURE

It doesn't make any pedagogic sense to attempt to teach the nuances of tone while glossing over the intricacies of articulation. How a singer shapes his or her vocal tract while singing will directly affect the quality of tone that is produced. It is also futile for the student of voice wishing to perfect tone, master registration, improve breath management, increase range and develop agility to avoid addressing how he or she uses and shapes his or her vocal tract.

A singer needs to find the configurations of the vocal tract (the resonator) that produce the exact acoustic characteristics dictated by the phonemes being sung. Because the entire vocal tract is relatively compact, any change among its components (lips, tongue, jaw, velum and larynx) has a direct effect on resonance balance.

In the following sections, I have attempted to address both the ideal and the incorrect shapes and positions for the individual components of the vocal tract. Please note, however, that since all of the individual parts of the vocal tract affect each other, it is difficult to discuss them in isolation.

For beginning singers, having so many parts of the vocal tract and so many elements of technique to focus on at the same time can be very overwhelming and stress inducing. Students need to remember to keep the back straight, the sternum elevated, the jaw collected (wrapped up and back), the tongue forward and out of the throat, the cheeks lifted under the eyes, the soft palate high and wide, the larynx low, the pharynx open, the velopharyngeal port closed during oral sounds, the mouth rounded, the jaw lowered in the upper passaggio, the vowels modified, etc., all while remembering to support the breath with the body. With an approach that seems so complicated and mechanical, it is not surprising that many students of voice find that lessons temporarily strip them of their enjoyment of singing. And it is no wonder that many impatient students opt for 'quick fix' vocal methods that don't make singing seem so involved, but that also don't produce the best and most healthy results in the long-term.

After making an initial assessment of a new student's skills (both the weaknesses and the strengths) and a diagnosis of any problems, a teacher and student team should begin to approach the correction of technical errors systematically, addressing one particular area of faulty technique at a time. By taking a step-by-step approach, the student won't be as overwhelmed, and progress will begin to be made almost immediately. Generally, by the time that the student is ready to move onto the next stage in his or her vocal development, the earlier steps to achieving a better singing voice will have become natural and automatic, and they won't have to give them much thought anymore. The foundation of his or her technique will become built one skill at a time.

When it comes to helping my students achieve optimal resonance balancing and vocal health, I tend to only address those elements of vocal posture that are hindering them from creating a fully resonant and healthy tone. Most students who come to me enjoy singing, and already possess some natural abilities. This means that much of what they are doing is likely to be correct. I acknowledge when they are doing something correctly with consistency so that they know to keep on doing it, then we move on to address, one by one, the problematic areas of their technique. In many cases, addressing one technical error automatically improves other areas of singing.

OVERALL POSTURE (THE HEAD, CHIN, NECK AND BACK)

A singer should begin with good bodily posture. He or she should stand up straight, with the shoulders back, the chin level and the head in a comfortable speaking position. The front of the neck should not be stretched, but loose. This posture will help put the jaw into the proper position for voice training, which, in turn, will improve vocal fold function. Breath support will also be improved.

Posture can be monitored using a wall, with the head looking straightforward. Maintain the slight, natural curves in the small of the back and in the neck. This will offer the correct head posture for singing in all registers.

During training or performances, it is also best not to keep the head turned to either side for any length of time. Although there may be some performance situations in which the head must remain turned (e.g., in musical theatre, in order to make eye contact with the audience while sitting at a piano, etc.), it is best to keep the head facing straight during all singing demands whenever possible.

If the singer must (or chooses to) sit while singing, it is important to keep the back straight, not hunched, in order to allow for better breath support. This is a big challenge for singers who play the guitar while seated, because they tend to lean over their instruments, curving the spine and bending the neck forward.

It is important to maintain proper chin posture, even when singing very high or very low notes. A chin that is comfortably positioned will ensure that the jaw remains properly aligned for optimal voice training. The head should be held neither too high nor too low but remain in the communicative position of normal speech. This consistent posture helps to create a more balanced voice training session and, eventually, a more pleasing performance.

There is a tendency amongst singers to employ low head positions during the execution of low notes and high head positions during the singing of high notes. However, the chin must not crane forward (jut out) or elevate for ascending pitch nor lower or tuck in for pitch descent, as these positions are unfavourable to the singing voice.

Raising the chin or head does not free the larynx. Nor does using the head to reach for high notes enable the vocalist to sing those higher pitches. Instead, tension is created, and accessing the upper register becomes more difficult, if not unlikely.

Likewise, a low head position presses the submandibular muscles downward on the larynx, creating tension and discomfort. This is a situation whereby singers depress the larynx with the jaw or chin, burying their chins into their larynxes, thinking that they are getting more color or darkness in the voice. However, the result is a non-resonant, 'hooty' and 'dark' quality that is not only unpleasant, but also fails to carry in a concert hall. A depressed larynx technique makes for an extremely limited vocal production that can never be heard to the extent of a fully resonant tone. For some singers, burying their chins into their larynxes seems to bounce their resonance off their sternums (chest bones). However, the audience does not hear the same sound in this posture.

The only way to produce healthy darkness in the voice is with the 'rounding of the vowels' that is achieved by using the oval mouth shape. (The concept of 'rounding the vowels' is covered in more depth in the section on vowel modification, in Vowels, Vowel Formants and Vowel Modification.) This lengthens the vocal tract and allows for a rounder and warmer colour to come into the singer's vocal production. (I also discuss correct mouth shaping in more detail in other sections of this article.)

In singers whose throats are 'closed', the sidewalls of the throat will sometimes 'collapse', where the neck muscles will curve inward, creating a half moon shape on each side of the neck, which means that the pharynx is collapsing.

FACIAL POSTURE

The quality of tone in the singing voice is directly affected by one's facial posture because of its effects on the interior posture of the throat. There is an acoustical relationship between correct facial posture and healthy tone that is balanced between higher and lower overtones. (See formants.)

Some singers pull down their cheeks, (or allow them to droop), and cover their teeth completely while singing, making singing difficult and 'hooty'. If the facial posture is pulled down, which also lowers the soft palate, then the singer must work twice as hard with breath pressure to blow the soft palate out of the way. The result is usually a pushed and unpleasant tone, with high notes that are flat in intonation.

A healthy facial posture is established when breath is taken. The cheeks should gently rise under the eyes. This action moves the uvula away from the back of the tongue, lifts the soft palate and prevents drooping of the cheek muscles. The cheeks should be sunken a little at the back molars, which opens the back wall of the pharynx, at inhalation. Finally, the jaw should be 'collected' gently back in order for the larynx to release downward. Using a mirror to self-supervise this facial posture exercise is helpful.

Having the zygomatic muscles follow patterns associated with pleasant facial expressions - be careful that you do not create a full smile, however - achieves an uncontrived adjustment of the entire buccopharyngeal (mouth-pharynx) cavity. It avoids unnatural attempts to create internal space where it is not possible to do so.

Without 'lift', the singer's voice does not carry properly in a concert hall or opera house because the Singer's Formant cannot be achieved. Lifting the cheeks under the eyes - not smiling, but assuming a pleasant expression - brings the soft palate up and brings ring into the voice, and therefore carrying power. Some vocal instructors may call this technique 'lifting', and may have their students practice singing with a pleasant expression on their faces. When the facial posture is lifted, high overtones - those which are necessary for the development of the Singer's Formant - come into the singer's vocal production.

THE SOFT PALATE

The action of the soft palate (velum) is a major focus of students wishing to 'open the throat' for singing.

During inhalation, when a singer is preparing to sing, the soft palate automatically rises, allowing more space for airflow. (This action can be observed by looking into a mirror while opening the mouth and inhaling.) For this reason, deep breathing is sometimes a successful device for relaxing the throat and preventing rigidity.

The key is to learn to maintain this initial elevated position while singing, not allowing the soft palate to lower substantially. Sustaining a high soft palate is particularly important while singing in head voice - in the upper passaggio and range above the staff. In upper range, the fauces elevate even more, with the soft palate following suit, just as happens in high-pitched laughter.

During singing and speaking in English, the velum is lowered only for the formation of nasal consonants. To suggest that the velum be held low during nonnasals is contrary to the laws of acoustics. If velopharyngeal-port closure is lacking during nonnasals, undesirable nasality intrudes. There is nearly universal agreement among phoneticians, speech therapists and teachers of singing that nasality, apart from intended, intermittent nasal phonemes, is unacceptable timbre.

The techniques of 'lifting' and imagining the neutral vowel 'uh' in the throat before bringing the tone into focus - both of which are outlined in the How To - And How Not To - Achieve An 'Open Throat' section - both encourage the lifting of the soft palate during inhalation and the maintenance of this initial elevated posture during singing.

LARYNX

Please note that the buccopharyngeal (mouth-pharynx) resonator plays a feedback role in laryngeal action, so the focus of the singer should be on the articulators not on the larynx itself. Attempting to exercise direct laryngeal controls causes the articulatory mechanism to malfunction and often leads to vocal health concerns.

The ideal position of the larynx during singing within lower and middle registers is relaxed and low. This position is achieved with every complete breath renewal. In other words, when a singer is preparing to sing (i.e., inhaling), the larynx naturally lowers. Gently place a hand on your larynx then inhale. As air enters the lungs, the larynx can be felt moving down a bit. (This action can also be observed in a mirror.)

Because of the increase in energy demanded, the larynx naturally adopts a slightly lower level for singing than for speech. It is the student of voice's goal to maintain this lowered position during singing in all parts of the range. As vocalizing begins, the larynx should not move upwards, although it will rock or 'tilt' (pivot) slightly when the head register is approached and entered.

Allowing the larynx to rise invites numerous problems with tone balance, registration, blending, discomfort, etc.. Higher pitches require more space, and an elevated larynx shortens the resonator tract, making higher notes more difficult to sing. With a high larynx, getting into the upper passaggio and the high vocal range is usually difficult because the folds can't pivot properly for the correct register changes to occur. The vocal folds also do not close properly. No part of the vocal tract, then, is in the correct position for healthy singing to occur.

Singing with a raised larynx will also produce a thin, innocuous timbre that lacks warmth and depth, as well as volume. A high larynxed technique generally produces what is often called a 'boys choir' sound.

Furthermore, poor technique, such as using too much breath pressure, may cause the larynx to rise and create a 'squeezing' of the throat, especially as pitch ascends upward into the head register, rather than a healthy 'ring' in the voice. Training to sing in a range or tessitura that is not natural for a singer's voice can also create issues with the position of the larynx. A lyric baritone, for example, will not be able to sustain a tenor tessitura with a lower larynx position. The result will usually be a squeezed or tight throat, which can be damaging (e.g., causing irritation to the vocal folds and possible injury). The singer is trying desperately to 'lighten up the voice'. This concept of lightening the voice needs to be taught with a deep body connection (breath support). The only way a large voiced singer can lighten up his or her tonal quality is to connect deeper to the body.

Some teachers advocate placing a hand just above the laryngeal prominence - (the laryngeal prominence is colloquially known as either the Adam's apple or Eve's apple) - after inhalation and holding the larynx in that lower position using the hand while singing, especially while ascending the scale. This is an injurious technique, as it may lead to bruising, as well as malfunction, of the larynx because it is being manually restrained from the outside and forced to remain in one position regardless of the pitch being sung or the linguistic requirements, (including vowels), of the text. Never in any kind of vocal training should the larynx, or any other part of the vocal tract for that matter, be physically or manually forced to 'behave'. Instead, training the larynx to remain relaxed and low should be approached safely (gently) and correctly, beginning with an examination and retraining of the other components of the vocal tract that may be affecting the position of the larynx, as well as the singer's breath management. (Again, the focus should be on the articulators, not the larynx itself.)

If the teacher has the student gently place his or her hand on the larynx while vocalizing, without attempting to manipulate or obstruct its movement from the exterior, for the purpose of having the student monitor the action of the larynx, such a practice is appropriate and safe. In fact, some students who are typically unaware of when their larynxes are rising until they feel extreme discomfort in the throat region gain more awareness of the vocal mechanism by either watching the movement of the larynx in a mirror or gently, (placing no physical pressure on it), monitoring it with their fingers.

If the larynx rises in the upper middle register, usually caused by a lack of the laryngeal tilt or 'rocking of the larynx' that must happen in the upper middle register and above in order for head voice to be accessed, tone will become thin and tight sounding. Head voice occurs as a result of the laryngeal tilt and if that tilt does not happen, then the singer will experience extreme difficulty in the upper passaggio. The singer can either think the vowel deeper and wider as he or she goes up, or alter the vowel enough to allow for this process to occur. (I will discuss vowel modification in greater depth in the second part to this article, to be posted in mid June of 2009.) Different singers respond differently and one might respond to the vowel alteration, while another might respond to the laryngeal tilt concept. Besides the laryngeal tilt, a singer may be instructed in the pre-vomit reflex - what the Italians called the vomitare - which will ensure that the laryngeal tilt will occur properly.

Equally unhealthy to the singing voice is a depressed (overly low) laryngeal position, as it can cause pathological problems for the voice. While the larynx does need to be relaxed and low during singing, a depressed larynx is both incorrect and damaging. The larynx should never be forced down, such as with the root of the tongue. It is crucial that the singer learn a slightly low larynx production without overly depressing the larynx with the root of the tongue.

If taught with the nasal resonance and the 'NG' tongue position - with the 'NG' formed with the middle of the tongue and the tongue tip in its correct resting place - the slightly lowered larynx makes for a healthy, warm, and balanced vocal tone that includes both higher and lower overtones.

THE LIPS

There are some teachers and choir directors who instruct their students or choir members to pucker their lips while singing. Pulling downward on the upper lip to cover the upper teeth alters the shape of the articulation system, and forces all vowels to become distorted. Try puckering your lips, as in the [u] position while singing the vowel [i] ('eeh'), and take note of how terrible it sounds. It destroys the chiaroscuro relationship among the harmonic partials, overly darkening the tone, and the vowel itself no longer sounds like an [i].

Furthermore, this technique creates tension and tightens the back of the throat. It affects buccopharyngeal (mouth-pharynx) space, creating less space for resonance and reverses the role of the zygomatic muscles, as they can't lift the cheeks, and thus the soft palate, when they are being pulled forward and down. It is also unnatural, looks strange, and creates phonetic and acoustic distortion.

During speech, lip postures vary somewhat from person to person. However, the lips should never be brought forward to sing as a fixed position. For both speaking and singing, the shape of the vocal tract is in constant flux, and there is no one ideal position of the mouth or the lips for either. If the upper teeth are visible during speaking, they should also be visible during singing.

THE JAW

Jaw tension is a very common complaint amongst singers, and it is often caused by incorrect posture of the jaw during singing and speaking. This tension, which will likely adversely affect vocal health over time, is a symptom of poor technique that will also manifest itself in an unpleasant, imbalanced tone.

The correct jaw position is slightly down and wrapped back. In Italian, this ideal singing posture is referred to as 'raccogliere la bocca', which translates as 'to collect the mouth'. It refers to the avoidance of excessive jaw dropping or jaw-wagging during singing, both of which are techniques that may cause the temporomandibular joints to pop out of their sockets. The natural processes of vowel and consonantal definition are inherent components of the historic raccogliere la bocca concept. These principles maintain harmonic balance, especially when singing in the speech-inflection range.

The jaw should be relaxed at all times during singing and speech. When singing, the jaw should be allowed to drop, but not push forward or down too far. It should feel as though it is hanging loosely and comfortably from its 'hinges' feeling space in between our back teeth. As the jaw lowers, the singer should keep the elevation of the zygomatic fauscia, which is accomplished by a pleasant facial expression.

The mouth should be opened only wide enough to get a full, resonant tone, but no wider. The idea that powerful singers open their mouths as wide as possible is a myth, as I will explain momentarily. Although singing requires opening the mouth wider than speaking does, exactly how wide depends not only on the specific vowel or consonant being sung, but also on the pitch and volume (dynamic intensity) of the note. To help facilitate correct jaw placement, singers can experiment to find the optimal mouth size for each sound that they sing. The size of the opening should be comfortable, change appropriately for the vowel being sung, and help you to produce optimal resonance and maintain diction.

One very common technique that many vocal instructors and choir directors teach involves dropping the jaw excessively. Choir members are generally encouraged to open their mouths widely because it is thought, though incorrectly, to help them singer louder and make their voices heard better by the audience by creating a more open space for resonation. However, forcefully dropping the jaw from the temporomandibular joint does not produce more space in either the pharynx or the larynx. Instead, dropping the mandible actually narrows pharyngeal space and forces the submandibular musculature to press downward on the larynx.

A mouth that is opened too widely creates a throat that is too closed. This technique of extreme jaw lowering contradicts, and will not be in line with, what is known about normal acoustical function. A jaw that is too low actually places tension on the larynx, lowers the soft palate and inhibits the effective closure of the vocal folds, which is the opposite of the desired effect.

Furthermore, dropping the jaw produces radical changes among relationships of the formants, in both low and high registers, causing a reduction in or elimination of the harmonics (upper partials) essential to balanced vocal timbre. When these formants are absent, the voice lacks resonance and thus carrying power. Less volume is produced, and the tone that is heard by the audience is often lacking the warmth of proper resonance balancing.

Some choir directors and vocal teachers also believe falsely that a larger buccal (mouth) opening will assist their singers with diction. Contrary to their thinking, excessive jaw dropping upsets natural phonetic processes, as a singer can't clearly articulate or pronounce words when the mouth is shaped in such an unnatural way, making clear diction impossible. A uniformly dull voice timbre is produced. Vibrancy is measurably reduced, and vocal brilliance is eliminated, regardless of the voice's intrinsic beauty.

Some choir directors who teach this technique actually aim to have their singers produce uniformity of timbre so that no individual voice stands out in a choir. This requires stripping the more resonant voices of the healthy overtones that make them stand out favourably. However, excessive jaw dropping - leading to an overly large buccal opening - is an unhealthy approach to achieving blending within a group of singers. Such a mandibular posture induces undesirable tensions in the submandibular region (muscles located below the jaw), and invites numerous problems with tone and registration. Furthermore, it produces what is widely known as the 'choir boy' sound - an immature vocal timbre that is lacking in presence and power, and that no adult singer should be asked or expected to produce.

Some teachers will even instruct their students to physically and forcefully hold down their lower jaws while singing, such as when they are told to make a perpendicular shield of the three middle fingers, then place them between the upper and lower teeth to keep the mouth opened as wide as possible. In addition to creating tension, pulling down on the jaw encourages the elimination of upper partials that ought to be present during all singing, but especially solo singing. There is no phonatory task in speech (in any language) that requires the extent of jaw lowering perpetrated by the three-finger-insertion method.

Furthermore, it creates tension, discomfort and pain, which may lead to chronic problems such as TMJ syndrome, a disorder which may include symptoms such as acute or chronic inflammation of the temporomandibular joints, pain, dysfunction (e.g., 'clicking' during chewing or speaking) and impairment (e.g., 'locking' of the jaw joints). A mandible (jaw) that is dropped from its socket - which is what happens when the mouth is opened too widely - is not relaxed. Dropping the jaw excessively, whether in a futile attempt to relax tension or to introduce additional depth or roundness by strengthening the first formant, invites TMJ.

We have two temporomandibular joints, one in front of each ear, connecting the lower jawbone - the mandible - to the skull. The joints allow movement up and down, side to side, and forward and back for biting, chewing, swallowing, speaking and making facial expressions. Although the jaw drops when the mouth is opened widely during laughter, it does not become unhinged, whereas in a fully distended yawn, or during vomiting, it does. If you were to place your fingers gently on your temporomandibular joints and pretended to chew, you would feel a small amount of movement of this joint. However, if you were to lower your jaw or push it forward beyond its normal range of motion, you would feel strong action of the joint as it comes out of its socket. This is the point where the jaw has been forced down too far, creating tension. You don't want to ever get to this point while singing, as maintaining such a position for a period of time will cause a large amount of tension at the laryngeal level.

In laughter, the mouth cavity and the vocal tract are indeed both enlarged, the fascia of the cheek region (mask) is elevated, the velum is raised, and the pharyngeal wall is expanded. In such a natural event, the jaw lowers considerably, but it does not drop out of its temporomandibular socket. Only in vomiting or strenuous regurgitation does the jaw lower extensively. Regurgitation involves an unfavourable rearrangement of pharyngeal space, and shuts off the phonatory mechanism - (the passageway for air, and thus the ability of the vocal folds to produce the voice, is shut off). The more that one assumes the buccopharyngeal vomiting posture, the more one diminishes the space of the pharynx (throat). Therefore, the lowered-jaw technique that some teachers espouse in an effort to improve voice resonance is both unnatural and stress inducing.

Some teachers have their students keep their jaws in relatively the same dropped position during all vowel changes. Often teachers and choir directors believe that it is simpler to instruct their singers to assume one mouth and pharynx posture though which all vowels must then be produced. However, since locking the jaw in one position does not promote the changing acoustic events of phonation, this technique distorts all the vowels through the entire range, destroying both diction and resonance balance. When singers attempt to maintain the same very wide 'oval' shape regardless of the vowel being sung, it is often referred to as the 'locked jaw' (or 'jaw locked open') position.

If the mandible is retained in one low position, all vowel sounds share a common quality of distortion. Holding the jaw in one lowered position produces uniform vowel and timbre distortions, which is in conflict with acoustic phonetics and the physiology of phonation. The changing postures of the lips, tongue, jaw, fascia of the zygomatic region, velum and larynx determine flexible articulation. No one of these contributors, including the jaw and tongue can be held in a set position without inducing strain and distorted voice quality. It should be recalled that there is no single ideal position for the mouth in singing; vowel, tessitura, and dynamic intensity are the determinants. The jaw must not be held in a static position.

There is no fixed resonator position in speech or in song. The jaw must be permitted mobility, allowing flexible adjustments for rapid phonemic and pitch variations, not retained in low or distended positions. The historical international school advocates assuming speech postures in the speech-inflection range (si canta come si parla, or 'one sings as one speaks'). In upper range, the mouth opens more, but the integrity of the vowel, (determined by the postures of the jaw, lips, tongue, velum and larynx), is still maintained, and the jaw never comes out of its joints. Many singers suffering from TMJ or jaw tensions recover from these conditions once proper phonetic postures are reestablished.

Healthy middle voice function cannot be achieved if the mouth is overly opened or the jaw locked in an open position. (Lower male voices seem to fall into the trap of over-opening and locking, and produce what is called in some circles the 'baritone bark'.) When the jaw is lowered, pharyngeal space is actually reduced. Furthermore, the tone that is produced is often thin or 'one-dimensional', as the balance of overtones is often affected.

There is a tendency for many singers to push their jaws forward, especially for higher pitches, or allow it slide forward when singing the [u] vowel sound. The forward jaw technique refers to a jaw position that is too low and then is thrust forward, often out of its sockets. Many students of voice develop a tendency to thrust the jaw forward out of the temporomandibular joints in an attempt to hear their own sound better inside their heads.

Placing the jaw in a distended posture, however, invites acoustical and phonetic distortion - voice timbre becomes drastically distorted - as well as malfunction of the vocal instrument. This mandibular posture produces several negative results. First, when the jaw is placed in a forward position, undesirable tension in the submandibular region (muscles located below the jaw) is induced. Second, the vocal folds approximate (close or come together) poorly, which causes breathiness and prevents the folds from functioning efficiently and healthily. Third, the tongue gets pushed back into the pharynx, filling up the primary resonator with tongue mass, creating a gag reflex at the tongue root and producing a throaty sound. Fourth, this technique elevates the larynx, which contradicts what the singer is trying to accomplish. With the larynx functioning in a high position, only a thin, immature sound is produced. A large 'break' in the voice (also due to the poor adduction of the vocal folds) is also produced. Fifth, normal velar (soft palate) elevation is inhibited, so the soft palate assumes a low position, often resulting in a nasally or thin tone.

There is also often not a healthy separation between jaw and tongue function, which makes the tongue tense and legato (an Italian word meaning 'tied together', suggesting that the transitions between notes should be smooth, without any silence between them) lines impossible to execute. The breath is often choked off by the root of the tongue, making the breath line unhealthy and inefficient. The large amount of tension at the root of the tongue also distorts vowels.

Since the back wall of the pharynx is closed, there also cannot be healthy resonance present in the voice, since most of the healthy high overtones are cut out. It is impossible to produce a healthy sound with the jaw protruding forward.

The mouth cannot be overly opened and still achieve vocal protection. Yet the jaw must be out of the way enough toward the upper passaggio for the correct register flips to occur. When a singer is out of balance, often from the hyperextension of the jaw (jaw thrusting forward out of its socket), the upper passaggio range is problematic.

Some students of voice who experience tensions in the jaw due to incorrect positioning of it find it helpful to work with a mirror. Feeling the jaw move slightly down and back and feeling the gentle chew of the jaw can correct this problem, and can also assist the singer in finding the correct function of the jaw. Also, placing the palm of the hand gently in front of the chin while singing may help the student to become more aware of when the jaw is moving forward. (The student needs to be careful not to restrict the natural and healthy movements of the jaw with the hand, though.)

When a singer needs to relax jaw rigidity, vowel sequences that are in accord with normal tongue and jaw postures can be useful. It may also help for a singer to allow the jaw to drop open as he or she forms his or her words instead of using his or her muscles to forcefully open the mouth. This is known as 'lengthening the jaw'.

THE TONGUE

Most singers, and even many vocal teachers, don't give enough consideration to the role of the tongue during singing. However, the position and shape of the tongue are critical elements of good vocal health and optimal acoustical resonance - the results being governed by the extent to which the tongue controls events of the resonator tube (the vocal tract), and by the tongue's effect on laryngeal efficiency.

Incorrect positions of the tongue are a leading cause of numerous technical and vocal health problems, including undesirable (dull, muddy, harsh or tinny) timbres, distorted vowels, unclear diction, and a depressed larynx leading to discomfort in the throat and an inability to access the head register.

For optimal results, the tip of the tongue should rest behind the lower front teeth during singing. The tip of the tongue should move from this ideal position only briefly in order to form certain consonants. The middle of the tongue should form an arch that must be allowed to move in order to shape the vowels as it naturally would, raising for closed vowels, such as [i], and lowering for more open vowels, such as [a]. The shape of the arch will change for different vowels, but the tip should remain in its 'home' position while singing all vowels. It will move quickly out of this resting place only for the production of consonants, but should return quickly.

Inhalation is also best executed with the tongue in this position in order to prepare more efficiently for singing. When singers inhale loudly - when they are 'noisy breathers' - it is often because the roots of their tongues are slipping back into their throats, closing off the passageway for air and choking the breath. Simply returning the tip of the tongue to its forward position during inhalation is generally enough to help a singer breathe more silently and efficiently.

You can examine your tongue position while looking into a mirror. With the tip of the tongue in its correct resting position behind the top of the lower front teeth, roll the tongue slightly forward in an arched position. Your tongue may not want to behave in this way, particularly if you are accustomed to allowing it to push back into the throat because it produces the exact opposite effect of the gag reflex. However, with practice, you will realize the brilliance of the sound that can be produced. Be sure not to roll the tongue too forward, though.

Using this position is not difficult, and the rewards are great. When the mouth space appears to be smaller due to its being filled with a forward and arched tongue, the back of the throat (pharynx) is actually much more open. When the tongue assumes a healthy, relaxed, arched posture (e.g., the 'NG' position, formed with the middle - not the back - of the tongue elevated), there is not likely to be tongue tension or throat soreness, and the open acoustical space will create a more pleasant vocal sound. Many technical problems, including those related to vocal registration, will often disappear.

Trying to use other tongue postures in an attempt to achieve more resonance does not allow for the proper shaping of the vocal tract and creates tongue tension.

Some teachers with a poor understanding of the physiology of the voice may instruct their students to artificially depress the tongue (i.e., with a tongue depresser) while looking in a mirror, and may even have them attempt to do so while vocalizing. However, flattening the tongue does not produce more space in the throat, nor more acoustical space for resonance. If the tongue is flattened in an attempt to find more acoustical space in the throat, the mass of the muscles at the back of the tongue (the tongue root) is forced into the pharynx (the back wall of the throat), the very part of the throat that the singer is attempting to open. The primary resonator - the pharynx - becomes filled with the tongue mass, and the voice sounds as though it is being muffled, and has a 'throaty'.

This 'flat tongued' approach creates an unpleasant tone that sounds large, harsh and forced, as well as poor enunciation, as the integrity of the pure Italian vowel sounds become sacrificed. Clear transitions from vowel to vowel are impossible. Healthy nasal resonance disappears, register changes, particularly as the singer ascends the scale, are impossible because the vocal folds are unable to pivot in a healthy manner. Loss of high notes (along with the ability to transition into head voice register) is a particularly common symptom.

One very critical vocal problem, especially for the mezzo-soprano, is that of over-stretching the throat space in the middle register. This feeling of an overly huge throat space often results from depressing the root of the tongue, which places pressure directly on the vocal folds, preventing them from approximating completely, and resulting in a large and problematic register break at the transition between the lower registers. The solution to this problem is to have the singer think less space in the middle register so that she can stretch in the upper passaggio and above. (I will be discussing vowel modification and vocal cover or protection in a follow-up to this article, to be posted in mid June of 2009.)

This practice of singing with a flattened tongue can be very abusive and lead to vocal damage such as vocal hemorrhage, nodules, polyps or bowed or scarred vocal folds, as a great deal of breath pressure is required in order for the voice to rise in pitch. This excessive and constant breath pressure irritates the delicate vocal folds, leading to hoarseness and an inability to phonate healthily.

Breath support often also needs to be addressed, as 'flat tongued' singers typically don't breath low enough in the body, usually because their breath gets choked by the tongue root, as I explained above. Their quick breaths are too high in the body. The tongue can be released, making low breathing more possible, by placing the tongue between the lips and taking a slow, nasal breath. With the tongue trained to be in a more forward position, it cannot bunch up, and the singing breath will generally drop much lower into the body.

A flat, low or retracted tongue posture, sometimes called a 'false cover' - see the section below for a better explanation of the technique of vocal covering as it specifically relates to tongue posture - can be corrected though studying with the 'NG' tongue position, as healthy nasal resonance (not nasality) can completely release tension at the root of the tongue. If the tongue gets bunched up in the back of the throat during singing, exercises involving arpeggios or scales with the tongue in the correct 'NG' position (relaxed, with the root of the tongue out of the throat and the sound being shaped with the middle, not the back, portion of the tongue, and the tongue being forward and arched in the mouth space) will usually correct the problem.

This concept can be applied to repertoire by slowly moving from the 'NG' to a vowel, lifting the soft palate away from the tongue-root in order to expand and invite the upper overtones. Once the vowel feel is established then this feeling may be kept for a line of text. At first the singer will sometimes feel uncomfortable and report an overly bright or harsh sound inside their heads. This is mainly due to the fact that the singer has a history of listening instead of feeling, which creates a false colour in their internal hearing. With practice, though, the warmth will come into the sound as the larynx and tongue separate in function. When the tension at the root of the tongue releases, then the singer can realize free flying tonal quality and complete freedom of the vocal mechanism. The color comes into the vocal production as the tongue releases.

For my students with tongues that persistently slip back into their throats, I sometimes have them try singing with their tongues sticking out between the lips - wrapped over the lower lip. The students will sing a 'ba' sound during three-note exercises or short scales or arpeggios. (They must beware and avoid the tendency to also allow the lower mandible to move forward along with the tongue, as this will create tension.) While a singer's tongue would never protrude this far during ordinary speaking or singing demands, assuming this forward tongue position for training exercises prevents the tongue from bunching up in the throat. For many students, this allows them to experience for the first time the feeling of the relaxed, open throat while singing, especially in the head register. Most can finally find freedom in and above the upper passaggio, accessing full head voice for the first time without strain or a thinning of the sound. Once they get a sense of how it feels to keep the tongue out of the way in order to allow the throat to open properly, they then attempt to achieve this same freedom of the throat with the tongue position that is appropriate for each vowel and consonant. For many students, this simple exercise is successful at quickly retraining their retracted or depressed tongues.

VOCAL PROTECTION AND THE POSTURE OF THE TONGUE AND LARYNX

Many singers and teachers have a poor understanding of the concept of vocal covering, or 'cuperto' in Italian, or 'darkening of the voice' that enables singers to correctly and healthily navigate registration changes. (I discuss vocal covering in more depth in Vowels, Vowel Formants and Vowel Modification.) This darkening of the vowels should not be achieved by employing the tongue root and the laryngeal muscles in an attempt to open the throat by jamming the tongue down on top of the larynx or by overstretching the outer laryngeal muscles. (This technique is sometimes called a 'throat heave'.)

The idea of darkening really means to open the authentic acoustical space. However, using the root of the tongue to create a 'cover' - called a muscular cover - puts pressure directly on the glottis where the vocal folds come together. The interior pharyngeal space actually closes when a singer uses a muscular cover, and tremendous pressure is then placed on the vocal folds by the root of the tongue.

If taught without close attention being paid to tongue posture, this technique often creates a depressed, flat-tongued production that results in an unacceptable and harsh sound. If the muscular cover has been engaged, the only choice for the singer to go high is to push a tremendous amount of breath pressure to force phonation. Using the muscular cover technique is extremely dangerous and is a difficult habit to break because this muscular cover is connected to the gag reflex in the back of the tongue. Unfortunately, it is a practice that is often taught in some schools of singing.

Oftentimes, singers, both male and female, confuse muscular pressure (usually from tongue and neck muscles) with an authentic open throat or pharynx (lifted and wide soft palate, open back wall behind the tongue, and a slightly lowered and wide larynx). They attempt to access the high range using a retracting tongue or pressing the root of the tongue, but instead end up losing the upper range due to a resulting high-larynx singing position. The voice loses its register blend and begins to sound like different voices rather than one smooth sound throughout the scale. A depressed tongue usually accompanies problems with vibrato, particularly the vocal wobble (an unhealthy and overly wide and slow vibrancy rate), as well as vowel distortion, a lack of 'ring' in the voice, which can make breath management difficult, and engagement of the laryngeal muscles in a futile attempt to shift the voice or make the voice flip registration.

'Cuperto' is associated with an open acoustical space that is stabilized through the training of the interior wall of the throat at inhalation. This training also involves the alteration of the vowel without using the tongue. The tongue should always speak the integrity of the vowel, even if the vowel is altered in the pharynx. If employed correctly, this concept of cuperto can protect the throat and encourage healthy singing. (Again, I will be discussing the concept of vocal protection, or covering the voice, further in the section on vowel modification in the upcoming follow-up to this article.)

A flat, low, or retracted tongue posture, sometimes called a 'false cover', can be corrected through studying with the 'NG' tongue position, the 'NG' being formed with the middle, not the back, of the tongue. As the larynx and tongue separate in function, the tension at the root of the tongue releases, and the singer can realize a much more balanced and pleasant tonal quality and be able to successfully navigate register changes.

FORMANTS AND TONE

The study of formants, or at least the acquisition of a basic understanding of them, is a vital part of vocal training, and should not be neglected by serious singers wishing to produce the absolute best vocals that they possibly can. The 'ring' or the 'focus' of the voice, which is reflective of balanced resonance, depends on the presence of acoustic strength in the upper regions of the spectrum. In other words, it can only be achieved if upper partials or overtones (formants) are present. How to encourage the presence of these overtones, and thus positively affect the quality of the tone produced, is an important skill for all serious singers to gain.

In the following sections, I will discuss the relationship between vocal tract shaping and tone - how correct articulation of vowels creates balanced, fully resonant tone that is marked by the presence of these vocal formants.

WHAT ARE FORMANTS?

Voiced sounds are acoustically rich, having many harmonics above the fundamental frequency (the lowest frequency of a complex sound, which corresponds to the unique pitch heard in such a complex tone). These harmonics or overtones are integer or whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency, and occur at roughly 1000Hz intervals. (Spectrograms are often used to visualise and track formants.) Put very simply, the complex sound of the voice resonates at different harmonic pitches. These resonance frequencies, each corresponding to a resonance in the vocal tract - the 'pipe' between the 'voice box' (larynx) and the mouth - are called formants.

Because of their resonant origin, formants tend to stay essentially the same even when the frequency (pitch) of the fundamental is changed continually. As I will explain in an upcoming article on vowels and vowel modification, all vowels have their own unique formant frequencies - they are defined by their distinct frequencies at the first and second formants - that don't change even when pitch changes. For example, the formant frequencies for the [i] vowel for any given voice are more or less constant and remain within very specific limits in the frequency range. For this reason, these vowel formants may be called 'fixed formants'. (These frequencies remain constant because the articulation of the individual vowels remains relatively the same regardless of pitch.)

The spaces above the vocal folds are a series of connected resonating chambers that filter the sounds that emanate from the voice source (the vocal folds inside the larynx). During speech production and singing, the source signal - the sound wave produced by the larynx - is filtered according to the morphology of the oral tract and of the articulators (e.g., tongue, jaw, lips, etc.). Therefore, formants are acoustic resonances of the vocal tract itself that result from the various dimensions of the vocal tract spaces.

Because the vocal tract is a complex acoustic tube resonator of varying sizes and shapes, and is highly adjustable - it's not a simple tube - it tends to emphasize and amplify some overtones (harmonic components) of the phonated sound and de-emphasize or dampen others. (The resonance frequencies of the vocal tract tend to emphasize a series of frequencies that relate to the size and shape of the vocal tract, although these frequencies are not sequential in their strength, as in the case with overtones of the phonated sound.)

The vocal tract resonator has different requirements for the sounds that try to pass through it, depending upon the frequency of that sound. Certain frequencies pass through the resonator easily and, as a consequence, are given a high amplitude. Because partials of various frequencies are transmitted through the vocal tract simultaneously, those that coincide with the formant frequencies are radiated from the lip opening (projected from the mouth) with greater strength than others. In other words, harmonics that fall at or near these resonance frequencies of the vocal tract pass freely through the vocal tract and are most efficiently radiated as sound, producing a formant. Therefore, formants appear as peaks in the spectrum of the radiated sound. (Harmonics whose frequencies are not close to the resonance frequencies of the vocal tract become weakened, forming troughs between the spectral peaks, and do not pass through the vocal tract.)

Some of the parameters involved in the filtering phenomenon that brings about the formant pattern are speaker specific. For example, the length of the pharynx and the size of the vocal chamber distinguish the timbre of women, men and children. (Adult females have shorter vocal tracts than adult males. Therefore their formant frequencies are fifteen percent higher on average than those of the adult male.)

The timbre of the voice strongly depends on the formant pattern (but it is also influenced by the signal's pitch), in particular on the first three formants. However, the same speaker can modulate a wide repertoire of sounds by changing the morphology of the vocal cavities, namely by displacing the tongue, opening the oral chamber to different extents, increasing its size by rounding and protruding the lips, letting the sound wave pass through the nasal cavity (instead of the oral one), or by lowering the velum (soft palate). All these parameters affect the formant pattern of the sound's spectrum, and the formant pattern enables us to distinguish between voiced sounds, in particular between oral vowels - an ordinary vowel without nasalisation.

Formants determine vowel quality and donate personal timbre to the voice. As well as determining perceived vocal quality, formants are important for the perception of personal voice quality, permitting us to identify individual voices, such as those of favourite singers on CD recordings or family members on the telephone.

In speech communication, our perception and labeling of certain sounds as vowels depends on the relationship of the lowest two formants. (In other words, the first two formants strongly contribute to the differentiation of vowels from one another.) For example, the 'roundness' or 'depth' - the 'oscuro' factor of the professional chiaroscuro timbre - of the sound results from the presence of strength in lower partials of the spectrum, termed the first formant.

Vowel 'colour' is also determined by the two lowest formants. It is defined mainly by the location in the spectrum of the changing middle formant - the second formant.

Timbre is determined by the third, fourth, and fifth formants.

When considering the different sounds produced during speech, usually just the first, second and third formants are considered, since these are the only formants whose frequencies tend to vary, (generally according to the vowel being sung).

There are generally five formants relevant to singing, though, and they are crucial in the perception and discrimination of voiced sound. In singing, contributions to the overall projection of sound are believed to be made by formants higher than the third. In fact, six or seven formants can often be identified in the laboratory. The higher formants are thought to contribute to the individual identity of the speaking or singing voice.

Swedish physician and medical researcher Johan Sundberg has identified an additional concentration or prominent cluster of intense acoustic energy, consisting of strong third, fourth and fifth formants. This cluster, which he termed the Singer's Formant, results from the cumulative distribution of upper harmonic partials (or overtones) that is present in the frequency spectra only of trained singing voices. This formant, which seems to be independent of the particular vowel and pitch, adds brilliance and carrying power to the voice. Tonal balance - or chiaroscuro timbre - is enhanced by, and results from, a proper distribution of energy among these three formant regions.

In the trained singing voice, considerable acoustic strength is present in both upper and lower regions of the spectrum regardless of the vowel being sung. The proper balance of this acoustic energy in upper, middle and lower portions of the spectrum ensures the classical resonance balance of the singing voice. The combining of these first two formants along with the cluster of formants - the third, fourth and fifth formants (generally referred to as the Singer's Formant that is found in some ranges of the singing voice in close proximity to the third formant) produces the ideal clear/dark tone of the historic chiaroscuro singing timbre. While the third formant - the Singer's Formant - produces the chiaro (light or clear) aspect of the historic chiaroscuro tone of the singing voice, it is largely the first formant that produces the balancing oscuro (dark) aspects.

FORMANT TUNING (RESONANCE TUNING)